NAT "KING" COLE

The legacy of Nat "King" Cole was built slowly and methodically. Regardless of initial intention, the building blocks were always being stacked, one upon another, towards eventual legendary renown. At first, he just wanted to be a pianist; vocals weren't a consideration. He found himself fronting a jazz trio, after which singing, for which he seemed most suited of the three, became a strong consideration. He broke through with a whimsical novelty song and took that route for awhile, sticking to his jazz roots as much as possible before advancing his profile (somewhat accidentally) with an exotic number one smash. The other two trio members were destined to be left behind as he embraced the vocal qualities he'd underestimated and began working with a variety of talented professionals. A second trio ran its course more quickly as he realized solo dominance was within reach; creative collaborations with top-notch musical arrangers enhanced this desire. His vocal sound became his trademark as ultra-romantic million sellers gained approval with white fans at a time when the public's tastes were largely segregated. Movie tie-ins, weekly television exposure and creative "concept" albums were additional pieces of the building block puzzle. With more than 20 years of continuous releases and a steady stream of hits (more than one hundred chart singles, a level few have reached), he achieved superstardom during the middle two decades of the 20th century. Then, a few years into the next eventful decade, it all abruptly ended.

Born in Montgomery, Alabama in 1919, Nathaniel Adams Coles (the middle name came from his mother, Perlina Adams) was never what you'd call a country boy. He lived in Chicago starting at the age of four; his father, Edward James Coles, was a baptist minister and young Nat got his first musical experience singing in church choir. His main focus (you could call it an obsession) was the piano. He didn't see himself as a particularly good vocalist and was surprised by the eventual acclaim. While placing a priority on mastering the many nuances of the keyboard, singing became something he did without much thought, which may account for the natural, easy sound he achieved. He'd been born a singer but didn't realize it until much later.

Family members developed the same interest: older brother Edward Bennett Coles (born in 1910) sang with Noble Sissle's band The Sizzling Syncopators starting in 1930. He formed his own band, Eddie Cole's Solid Swingers, in 1936; 17-year-old Nat played piano on "Thunder," the first of two Decca 78s. Younger brother Isaac "Ike" Cole (born in 1927), a drummer, bassist and pianist, formed his own jazz trio in the early 1950s and made occasional recordings for Bally, United Artists, Dot and a few other companies. Freddy Cole (born Lionel Frederick Cole in 1931) was, like his siblings, a pianist. In the '50s and '60s he made records for Okeh, Sue, Dot and several other labels.

Nadine Robinson of East St. Louis was ten years older than Nat; a dancer, they met while she was performing in a 1936 touring revival of Eubie Blake's 1921 musical Shuffle Along (Nat also had a small role in the cast). They were married in January 1937 and shortly afterwards the show ended in Los Angeles. The newlyweds remained in the area and over the next few years he performed as Nat Coles throughout Southern California, wherever he could find work, logging time in many out-of-the-way dive bars. A turning point occurred when the great jazz vibraphonist Lionel Hampton introduced him to two expert musicians. Guitarist Oscar Moore, originally from Austin, Texas, had already put in time with several jazz bands and impressed Nat immediately. Local double bass player Wesley Prince (he was from Pasadena) had backed Louis Armstong on some studio sessions, that one credit on his resumé enough to cinch his inclusion.

Bob Lewis, the owner of the Swanee Inn on La Brea Avenue in Hollywood, booked the trio on the condition they hire a drummer. Lee Young (brother of star saxophonist Lester Young) was tapped for the spot but didn't show up the first night, later claiming the tiny club didn't have enough space for his drumkit (truth was he'd gotten a gig with a larger, better-known band). So they remained a trio and Nat was fine with it, figuring the whole set-up would be a temporary one. Turns out it lasted over a decade. One night, Lewis placed a crown on Nat's head as an "Old King Cole" gag; Prince, who not surprisingly was fond of "royal" sounding names, urged the guys to go with it and The King Cole Trio (necessitating the "s" be dropped from Nat's last name) was used from that point on (though the gimmicky crown was discarded). The three complemented one another, taking turns on solos. Soon the word got out about this hot new act.

The first recordings were transcription discs for radio airplay; in 1938 they received limited exposure on national broadcasts. Decca Records signed the Trio in 1940 for the label's "Sepia Series" targeting African-American listeners. On December 6 of that year they recorded the Cliff Burwell-Mitchell Parish song "Sweet Lorraine" ('Just found joy, I'm as happy as a baby boy-be-boy, with another brand new choo-choo toy"), Nat's vocal revealing the unique sound that would serve him well (once he accepted the notion of singing regularly, which took some time). It was a fabulous start to a long, fruitful recording career. The Trio began playing clubs in New York around 1942, among them Kelly's Stables on 52nd Street, where many of the era's top acts appeared. While gigging in Los Angeles they met Carlos Gastel (who'd first seen them perform in '38); he became their manager partly on the basis of his ability to get them booked into larger clubs. The Trio received one thousand dollars per week to play the Orpheum, more than four times the amount they'd earned anywhere else.

Going on the road brought more challenges than they'd faced at the L.A. and N.Y. nightclubs; usually they stayed in seedy motels or sometimes with black families while entering and leaving the clubs through back entrances. On returning to L.A., Nat's profile made minor advances; he had an uncredited onscreen appearance as a club pianist in Orson Welles' Citizen Kane and the King Cole Trio made several other film appearances over the next few years. Decca failed to renew the group's contract (as with many artists, contracts are sometimes voided at the two-year mark, a common duration for first-time signees), then in early '43 the Trio's recording of "That Ain't Right" (an original penned by Nat) reached number one on Billboard's Harlem Hit Parade (the first incarnation of what became the rhythm and blues best seller chart), amounting to an error in judgment among Decca's executives (16 songs, issued on eight discs, comprise the entire Decca catalog). Later in the year, the Trio recorded "All For You" for Excelsior Records (they also had 78s on the Atlas and Premier labels during this time) and it became their second HHP topper in November.

Johnny Mercer and Glenn Wallichs had been aware of, and impressed by, the Trio since the late 1930s. The two founded Capitol Records in Hollywood in 1942; Gastel made arrangements for the Trio's signing around the time "All For You" took off in '43. The first discs on Capitol were reissues of the hit and "I'm Lost" (penned by Excelsior owner Otis René, it became their third chart single). Cole made a rookie mistake, selling half the publishing rights to his song "Straighten Up and Fly Right," a tune the Trio had performed in the film Here Comes Elmer, to music publisher Irving Mills for a mere 50 dollars. The crazy novelty about a conflict between a buzzard and a monkey ('Ain't no use in divin'...what's the use in jivin'?'), recorded at the first Capitol session, was their breakthrough to mainstream audiences, a top ten pop hit that spent ten weeks at number one on the Harlem Hit Parade in the spring and summer of '44; it even reached the top of the folk (later changed to country and western) chart.

Cole obliged his initial 88-key passion on July 2, 1944 at a spectacular concert in Los Angeles, Jazz at the Philharmonic, under a pseudonym, Shorty Nadine (using part of his wife's name). It was an "all star" event with tenor sax master Illinois Jacquet, up-and-coming innovator Les Paul on guitar, Jack McVea on sax, trumpeter Shorty Sherock, trombonist J.J. Johnson, bassist Johnny Miller, tuba player Red Callender and drummer Lee Young. An impressive series of King Cole Trio hits unfolded over the next few years, many of them whimsical and delightful. "Gee, Baby, Ain't I Good to You?" became the act's fourth number one Harlem Hit Parade disc in October 1944 (several months before the chart had a title change to "Most-Played Race Records"). In March 1945, Billboard introduced its Best-Selling Popular Record Albums chart and the sales levels of Capitol's eight-song set The King Cole Trio gave it the honor of being the chart's first number one, where it remained for 12 weeks; a second volume hit the top the following year. "It's Only a Paper Moon," "If You Can't Smile and Say Yes," "I'm a Shy Guy" and "Come to Baby, Do" kept them at the forefront during 1945 and '46, though mainly among black record buyers. A rousing rendition of Bobby Troup's "Get Your Kicks on Route 66" broke big in the summer of '46 on its way to classic status.

Exposure on national radio increased with the Trio's 1946 summer replacement stint on Bing Crosby's Kraft Music Hall series; then they hosted their own radio show, sponsored by Wildroot Cream Oil, for the next three years. A double-impact crossover took place later in '46; "(I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons," a more serious romantic song than its immediate predecessors, was written by Deek Watson (of legendary vocal group The Ink Spots) and Pat Best (later a member of '50s act The Four Tunes). Cole hit a vocal "sweet spot" with this one, reaching number one on the pop charts for the first time as a result. Immediately the Trio scored with an even bigger recording (assuming everlasting popularity counts for something); singer Mel Torme had composed "The Christmas Song" with Robert Wells and found in Cole the ideal interpreter of lyrics like 'Chestnuts roasting on an open fire...Jack Frost nipping at your nose...' It was their first recording with strings (arranged by Charles Grean), a hesitant step in the direction opposite that of a "jazz purist" position. The song became a perennial favorite and has remained popular ever since.

Fate led him to the Zanzibar nightclub at 49th and Broadway in Manhattan, where he met Maria Ellington, who for a short time had been a singer in Duke Ellington's band (the two weren't related; she had previously been married to Spurgeon Ellington, an Army airman who'd died during a training flight). This was in 1947, when one of the Trio's hits was "Meet Me at No Special Place (And I'll Be There at No Particular Time)"...coincidence? Nat left his first wife of eleven years and married Maria in March 1948, just six days after his divorce became final; the ceremony was performed by Reverend Adam Clayton Powell. The couple stared trouble in the face after purchasing a home in L.A.'s all-white Hancock Park district. Neighboring property owners banded together to try to keep them out. Someone resorted to Klanlike conduct by vandalizing their lawn. But the Coles stood their ground; adopted daughter Carole (actually their niece, as her mother, Maria's sister, had recently passed away) and birth daughter Natalie Cole (born in 1950) spent their early years dealing with what could be described as a terrifying situation to a young child.

In 1948, Cole began working more regularly with orchestras and string sections in a deliberate move towards pop music dominance. Moore quit soon afterwards and joined his brother Johnny Moore in The Three Blazers, a group that enjoyed a few huge R&B hits with lead singer Charles Brown. When Prince left, replacements came on board (not so much star-billed as notable backing musicians). Guitarist Irving Ashby and L.A. bass player Joe Comfort covered the two main spots; a fourth member, Chicago-born bongo player Jack Costanzo, was added mainly for touring, though not all concertgoers were impressed by his skin-slapping solos; jazz critics were tough on him, too. And the fact he was white caused issues on the road, forcing him in many cases to find separate accommodations from his bandmates.

Cole met Stan Kenton's musical director Pete Rugolo and the two were a good match; both enjoyed experimenting with new styles while tempering these admitted pleasures with a commercial lean. "Nature Boy" was written by Eden Ahbez, a "pre-hippie" of sorts who largely shunned the materialistic lifestyle most Americans sought (particularly after the end of World War II). Capitol had such a lack of faith in the song that they placed it on the B side of "Lost April" from the Oscar-winning motion picture The Bishop's Wife. But Ahbez's song about '...a very strange enchanted boy' sparked the public's imagination. Nat only did the singing on this track, arranged by Frank DeVol with unrelated pianist Buddy Cole. Credited simply to King Cole, the irresistible recording rode the top of the charts from May to July 1948, his best-selling disc to that point in time.

Hits of 1949 and '50 included "Kee-Mo Ky-Mo (The Magic Song)" from the album King Cole for Kids, a cover of Ivory Joe Hunter's "I Almost Lost My Mind" and a cover of Larry Darnell's "For You, My Love" in a duet with "Real Gone Gal" Nellie Lutcher. When "Mona Lisa" by the songwriting team of Jay Livingston and Ray Evans (from the film Captain Carey, U.S.A.) came up as a potential single, Nat was not impressed. He preferred "The Greatest Inventor (Of Them All)," recorded with Les Baxter's gospel-influenced chorus. But Nat's instincts were off-base; the B side developed with a life of its own and the six month chart run of "Mona Lisa," with four of those months spent in the number one or number two position, marks the softly-rendered recording as one of his biggest. Though credited to Baxter, this side was arranged by Nelson Riddle, the soon-to-be famous conductor-producer who would be a key component in Cole's early '50s success.

A collaboration with Stan Kenton came next. "Orange Colored Sky" (written by accordionist Milton Delugg) was arranged by Pete Rugolo, who'd worked extensively with both Kenton and Cole. He gave the song a hard-to-ignore exclamatory backing chorus ('Flash! Bam! Alakazam!') and the finished take became one of Cole's biggest hits. Nat's smoking habit had gradually made his voice deeper and grittier and he liked the sound of it; also he never got into the habit of resting his vocal cords like he should, convincing himself it was necessary to achieve the desired result. The newer lineup of the King Cole Trio lasted a much shorter time than the first, which continued with Ashby and Comfort for several more months before it was decided Cole would henceforth be billed as a solo act. At that point, his music drifted further from the jazz trio style and closer to the mainstream. He believed he'd found the path to lasting stardom by attempting a string of pop hits. He wasn't entirely wrong; some of his most popular and durable recordings came over the next five or six years.

Less than a year after "Mona Lisa," he had another hit of similar magnitude. Songwriting team Sid Lippman and Sylvia Dee (of "Chickery Chick" fame) wrote the ultra-romantic summer '51 hit "Too Young," Nat's fourth to reach the pop chart summit. Riddle arranged this one as well, and the two began working together more frequently. Opportunities for video exposure increased as TV viewing became the nation's leading pastime; in 1951, he was on an episode of the top-rated show, Milton Berle's Texaco Star Theatre on NBC. Recent Emmy winner Berle was pressured by network bosses to keep him off the show for fear of losing viewers, but Uncle Miltie exercised his clout as TV's top star. Cole went on and there were no repercussions. He made further appearances the next couple of years on The Jackie Gleason Show and The Red Skelton Hour.

One of Riddle's most effective arrangements was on "Unforgettable," an early 1952 hit that remained in people's memories and thus lived up to its title. Another Riddle gem, "Somewhere Along the Way," was a top ten summer hit. He began working occasionally with bandleader-arranger Billy May, who he'd known since the early days of the original King Cole Trio, resulting in the 1952 hit "Walkin' My Baby Back Home" (emotive crooner Johnnie Ray scored with his version at the same time). Taking a shot at acting, Nat had a role in Song For a Banjo, an episode of Lux Video Theater broadcast December 15, 1952. The Riddle-arranged "Pretend" was Cole's best seller of 1953. In '54 he scored with a German song, "Mütterlein," penned by Gerhard Winkler and Fred Rauch, translated as "Answer Me, My Love," with English lyrics by Carl Sigman. He gave Charlie Chaplin's "Smile" the NKC treatment, then put out a fun duet with Capitol labelmate Dean Martin at the end of the year: "Open Up the Doghouse (Two Cats Are Comin' In)."

Songs like "The Ruby and the Pearl" by Livingston and Evans and the Ned Washington-Dimitri Tiomkin movie theme "Hajji Baba," examples of an exotic, mystical middle-eastern style that came in the wake of "Nature Boy," were trendy in the early '50s. A French song, "Darling Je Vous Aime Beaucoup," written in 1936 by Anna Sosenko, had become popular as the signature song for Wisconsin-born Hildegarde ("The Incomparable"); Cole's top ten remake inspired him to record other foreign language songs (usually combined with English lyrics) over the next few years. He and orchestra leader Les Baxter teamed on a series of hits while Nelson Riddle began working with recent Capitol signee Frank Sinatra using a similar approach that brought "Ol' Blue Eyes" back into the spotlight.

Nat's hits in 1955 included "A Blossom Fell" (which reached number two, held off by a new-fangled kind of song by Bill Haley and his Comets called "Rock Around the Clock") and "If I May," the first of several with backing vocals by breakthrough Capitol quartet The Four Knights. The Nat "King" Cole Musical Story, an 18-minute Technicolor/Cinemascope documentary short, was brief on background history and more focused on his performances. It was released to theaters in December 1955. His singles from 1956 climbed high on the charts yet fell short of the top ten despite undeniable appeal: "Ask Me" and "Too Young to Go Steady" were followed by another smooth Four Knights number, "That's All There is to That," and the two-sider "Night Lights" and "To the Ends of the Earth," the latter sounding as globe-spanning as its title. Maria Cole signed a contract with Capitol at this time (she'd done one album for Kapp Records two years earlier), but there were only two singles; ten years later the label gave her another shot with a full album.

Racial discrimination continued to be an issue for Nat (any many others, of course) during the 1950s; it didn't necessarily matter how big a star he'd become. During a 1956 show in Birmingham, Alabama he was harrassed and physically attacked by a self-described "White Citizens' Council." The offenders were arrested on the spot and he managed to finish the set, but then canceled several upcoming appearances, during which time he went to Chicago to be with his father and decompress. Publically, he didn't make a big deal of it, which irritated NAACP chief counsel (and later associate Supreme Court justice) Thurgood Marshall, who disrespectfully compared him to Uncle Tom. The owners of the Sands in Las Vegas, an integrated hotel and nightclub, offered a far better situation, guaranteeing a no-hassle stay for him and his entire crew, regardless of color. He made it a point to perform there whenever possible and continued to do so thoughout his remaining years.

In 1956, he indulged his jazz preference with After Midnight, an album featuring Sweets Edison on trumpet, Willie Smith on alto saxophone, Stuff Smith on violin and Juan Tizol on trombone. Then in November of that year he became the first black singer to host a weekly TV variety series. 53 installments of The Nat 'King' Cole Show were broadcast on NBC, originally running 15 minutes before expanding to 30. The show was canceled in December 1957. Afterwards he received a great deal of press with his comment "Madison Avenue is afraid of the dark." He never even appeared on the cover of TV Guide, yet all the white stars seemed to have no problem pulling it off (that first-time "honor" for a black television star finally went to Bill Cosby in 1966, during his time as the co-star of I Spy, another NBC series). Movies seemed a better bet; he secured an acting role in the 1957 crime drama Istanbul starring Errol Flynn and another in the war film China Gate with Gene Barry and Angie Dickinson, for which he also sang the title theme.

1957 was a year with a couple of career milestones. First-time stereo LP Love is the Thing, with Gordon Jenkins arranging, was a number one album (the first since the initial two volumes of The King Cole Trio in '45 and '46) based in part on the inclusion of a heartfelt, string-drenched remake of "Stardust," the late '20s Hoagy Carmichael-Mitchell Parish classic. "Send For Me," the closest he ever came to a rock and roll number, became an airplay magnet at early top 40 radio stations. Featuring backing vocals by session singers identified as McCoy's Boys (on this and follow-up "With You on My Mind"), it took off like a rocket, getting him into the national top ten for the first time in two years.

St. Louis Blues, his first and only leading role in a theatrical motion picture, had its premiere in April 1958. A heavily fictionalized biography of early 20th century blues pioneer W.C. Handy, the film included several original Handy songs by Cole and/or co-stars Eartha Kitt and Pearl Bailey in addition to a couple of gospel numbers by Mahalia Jackson. Many critics were harsh in their reviews, but over the years the film has taken on historical significance for its cast and music. Nat took another single into the Billboard top ten during the summer: "Looking Back," composed by Clyde Otis, Belford Hendricks and soon-to-be hitmaking singer Brook Benton (whose style was often compared to Cole's). The first Grammys were handed out on May 4, 1959, its inital batch of awards for 1958 releases; Cole garnered a nomination for "Looking Back" in the category Best Rhythm and Blues performance. Curiously, it lost to the instrumental "Tequila" by The Champs, one of literally hundreds of head-scratching, "what the-?" categorical oddities that have continued right up to the most recent year's awards.

The Spanish language LP Cole Español furthered Nat's interest in international songs. His 1958 hits included part-English recordings "Come Closer to Me (Abercate Mas)," a Mexican song from 1940, and "Non Dimenticar (Don't Forget)," an Italian song featured in the 1951 film Anna starring Silvana Mangano. His next acting role was in Night of the Quarter Moon, a vehicle for singer-actress Julie London, released to theaters in March 1959. A few months later, Nat and Maria adopted a child, their only son, Nat Kelly Cole. Television appearances and performances became more common in the late '50s and early '60s; Nat was on The Eddie Fisher Show, The Patti Page Oldsmobile Show, The Pat Boone Chevy Showroom and The Dinah Shore Show and made dozens of appearances on the top-rated Ed Sullivan Show and Perry Como's Kraft Music Hall. Hit singles were scarce in the first couple of years of the new decade; one standout is the mostly-instrumental "Whatcha Gonna Do," an original by Nat that simultaneously showcases his skill as a jazz pianist and pop performer.

The Grammy Awards always made an effort to include him among the nominees, even if they had to come up with weird categories in order to make it happen. For the 1959 season (covering January through August), he received two nods. The brilliant "Midnight Flyer" won the award for Best Performance by a Top 40 Artist (ignoring the fact that the song never made the top 40 and the other nominated songs were much bigger hits). The bizarre category, acknowledging a fairly new radio format, only existed this one year. And it was the only Grammy Cole won during his lifetime. Wild is Love, a concept album orchestrated by Nelson Riddle with 14 tracks that unfold much like a cast or soundtrack recording, received two nominations in 1960 including Album of the Year. In '61 he was up for Album of the Year again - another head-scratcher, depending on your perspective - for The Nat "King" Cole Story, a three-disc set with 36 tracks, all stereo re-recordings of hits originally in mono.

Lee Gillette, a fellow Chicagoan and close friend of Nat's, produced the majority of his sessions in the '60s, but there were a few notable exceptions. "Ramblin' Rose," a "modern country"-style pop song penned by Brooklyn-based brothers Joe and Noel Sherman with an arrangement by Belford Hendricks was a giant hit, reaching number two in the fall of '62 (behind The 4 Seasons' breakthrough, "Sherry") and topping the recently-established Easy Listening chart for five weeks. It got him another Grammy nomination, this time for Record of the Year (Tony Bennett emerged victorious for a song about a certain city by the Bay). If you're keeping track, that's seven nominations total, one win (plus another citation many years later for lifetime achievement). Add on a win at the '63 Golden Globes if you like, a special award "for international contribution to the recording world." Hendricks arranged two more hits for Cole in the following months: "Dear Lonely Hearts" and "All Over the World."

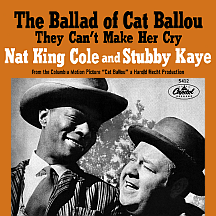

A similar cycle took hold a year later. Under the musical direction of Ralph Carmichael, Cole enjoyed one final top ten hit, "Those Lazy-Hazy-Crazy Days of Summer," an old-timey singalong inspired by Mitch Miller's popular albums and television series Sing Along With Mitch. Two others with Carmichael carried him through the coming months: the similarly-conceived "That Sunday, That Summer" and folkish "My True Carrie, Love." In January of '64, Jack Benny welcomed Cole on an episode of his weekly comedy series; Nat sang and participated in a skit with Jack. In the fall of '64, the Bert Kaempfert-Milt Gabler song "L-O-V-E" appeared, forever associated with the "King." At this time, Nat was appearing in Lake Tahoe while filming his segments of Cat Ballou (a western comedy starring Jane Fonda and Lee Marvin). He and Stubby Kaye played wandering minstrels performing the film's theme by Jerry Livingston and Mack David, which was nominated for an Oscar for Best Original Song. Traveling back and forth, the routine was fatiguing and he was losing weight. Or perhaps it wasn't the schedule that caused these things.

Cole, a heavy cigarette smoker, died of lung cancer in February 1965 at a younger age than most; one of the 20th century's greatest performers robbed himself of many productive, vibrant years - cancer sticks, upwards of a half-million of them, ended his 45-year life. Yet the public had enjoyed his exquisite talent for over 25 years...and modern listeners have inherited an incredible life's work to cherish for as long as our planet continues to exist.

I met Natalie Cole in 1989 at an event held by the radio station I was working for at the time. I asked her a question, though it turned out I wasn't the first to do so: "Do you think you might ever record some of your father's songs?" to which she replied with a smile, "A lot of people have asked the same thing, so maybe I should consider it." Two years later, the album Unforgettable with Love was released by Elektra Records, the "with love" part of the title evident in the joyous way she delivered each of the set's 22 recordings of songs made famous by her legendary father (her uncle, Ike Cole, played piano on the sessions). The capper was the hit that supplied the other word in the album's title: "Unforgettable" used his vocals from the stereo 1961 version of the song; Natalie's contribution to the duet was seamlessly dubbed in. The song placed high on the charts, marking Nat "King" Cole's first hit since his death 26 years earlier. The album spent six weeks at number one that summer, going on to sell over six million copies and win six Grammy awards (two of them adding to Nat's Grammy total) including Record of the Year, Album of the Year, Best Traditional Pop Performance and Song of Year (for 77-year-old Irving Gordon, who'd composed "Unforgettable" more than 40 years earlier). I guess that was a pretty good idea those many fans, including myself, came up with. I'm confident everyone's glad she took our advice.

NOTABLE SINGLES:

- Thunder - 1936

by Eddie Cole's Solid Swingers (Nat Cole on piano) - Sweet Lorraine - 1941

by King Cole Trio - That Ain't Right - 1942

by King Cole Trio - All For You - 1943

by King Cole Trio - Straighten Up and Fly Right - 1944

by the King Cole Trio / - I Can't See For Lookin' - 1944

by the King Cole Trio - I Realize Now - 1944

by the King Cole Trio / - Gee, Baby, Ain't I Good to You? - 1944

by the King Cole Trio - I'm Lost - 1944

by King Cole Trio - It's Only a Paper Moon - 1944

by the King Cole Trio - If You Can't Smile and Say Yes - 1945

by the King Cole Trio - I'm a Shy Guy - 1945

by the King Cole Trio - The Frim Fram Sauce - 1946

by the King Cole Trio / - Come to Baby, Do - 1946

by the King Cole Trio - Get Your Kicks on Route 66 - 1946

by the King Cole Trio - You Call it Madness (But I Call it Love) - 1946

by the King Cole Trio - (I Love You) For Sentimental Reasons - 1946

by the King Cole Trio - The Christmas Song (Merry Christmas to You) - 1946

by the King Cole Trio - Meet Me at No Special Place (And I'll Be There at No Particular Time) - 1947

by the King Cole Trio - Those Things Money Can't Buy - 1948

by the King Cole Trio - What'll I Do? - 1948

by the King Cole Trio - Nature Boy - 1948

as King Cole / - Come to Baby, Do - 1948

by the King Cole Trio - Kee-Mo Ky-Mo (The Magic Song) - 1949

by the King Cole Trio - Flo and Joe - 1949

by the King Cole Trio - Exactly Like You - 1949 /

as Nat "King" Cole and the Trio / - My Mother Told Me - 1950

as Nat "King" Cole and the Trio - For You, My Love - 1950

by Nellie Lutcher and Nat "King" Cole - I Almost Lost My Mind - 1950

by the King Cole Trio - Calypso Blues - 1950

- Mona Lisa - 1950

- Orange Colored Sky - 1950

by Nat "King" Cole and Stan Kenton - Jet - 1951

- Too Young - 1951

- Red Sails in the Sunset - 1951

- Unforgettable - 1952

- Somewhere Along the Way - 1952

- Walkin' My Baby Back Home - 1952

by Nat "King" Cole and Billy May - Funny (Not Much) - 1952

- Because You're Mine - 1952

- Faith Can Move Mountains /

The Ruby and the Pearl - 1952 - Pretend - 1953

- Can't I? - 1953

by Nat "King" Cole and Billy May - Answer Me, My Love - 1954

- Smile - 1954

- Hajji Baba (Persian Lament) - 1954

- Open Up the Doghouse (Two Cats Are Comin' In) - 1955

by Dean Martin and Nat "King" Cole - Darling Je Vous Aime Beaucoup /

The Sand and the Sea - 1955 - A Blossom Fell - 1955 /

- If I May - 1955

by Nat "King" Cole and the Four Knights - My One Sin - 1955

- Someone You Love /

Forgive My Heart - 1955 - Take Me Back to Toyland /

I'm Gonna Laugh You Right Out of My Life - 1956 - Ask Me /

Nothing Ever Changes My Love For You - 1956 - Too Young to Go Steady /

Never Let Me Go - 1956 - That's All There is to That - 1956

by Nat "King" Cole and the Four Knights / - My Dream Sonata - 1956

- Night Lights /

To the Ends of the Earth - 1956 - Ballerina /

You Are My First Love - 1957 - When Rock and Roll Come to Trinidad - 1957

- Stardust - 1957

- Send For Me - 1957 /

My Personal Possession - 1957

by Nat "King" Cole and the Four Knights - With You on My Mind - 1957

- Angel Smile - 1958

- Looking Back /

Do I Like It - 1958 - Come Closer to Me (Abercate Mas) /

Nothing in the World - 1958 - Non Dimenticar (Don't Forget) - 1958

- You Made Me Love You /

I Must Be Dreaming - 1959 - Midnight Flyer - 1959

- Time and the River /

Whatcha Gonna Do - 1960 - My Love - 1960

by Nat "King" Cole and Stan Kenton - Take a Fool's Advice - 1961

- Let True Love Begin - 1961

- Ramblin' Rose - 1962

- Dear Lonely Hearts - 1962

- All Over the World /

Nothing Goes Up (Without Coming Down) - 1963 - Those Lazy-Hazy-Crazy Days of Summer - 1963

- That Sunday, That Summer - 1963

- My True Carrie, Love - 1964

- People /

I Don't Want to Be Hurt Anymore - 1964 - I Don't Want to See Tomorrow /

L-O-V-E - 1964 - The Ballad of Cat Ballou - 1965

by Nat "King" Cole and Stubby Kaye - Let Me Tell You, Babe - 1966

- Unforgettable - 1991

by Natalie Cole with Nat "King" Cole