ARETHA FRANKLIN

The most important period in Aretha Franklin's career as a singer was from 1960 to 1967, the years she spent with Columbia Records along with the early months of her association with Atlantic. Without the experience she gained during those Columbia years, performing and recording all manner of pop and blues, R&B, show tunes and ultimately the soul music she mastered so spectacularly, Aretha would not have become the superstar and, indeed, national treasure that she is. Not everyone agrees with my opinion on this. Aretha possessed impressive vocal range and control at an early age, but she was not a fully-formed artist in her teens; if anything she was a very good gospel singer with the potential for more. Don't believe anyone who tells you her time at Columbia was meaningless or unnecessary. It was essential. The producers, arrangers and A&R men she worked with during those years helped develop her and lead the way to the great levels she would later achieve.

Her history begins in 1942 in Memphis, Tennessee, but it doesn't linger there long. Her family made a couple of moves and settled in Detroit when Aretha was four. She had an uncanny knack for playing the piano by ear and later said that Eddie Heywood, an accomplished jazz pianist best known for the huge 1956 hit "Canadian Sunset" with Hugo Winterhalter's orchestra, was her main influence. Along with older sister Erma Franklin and younger sister Carolyn (both of whom would also become accomplished recording artists), she sang in the New Bethel Baptist Church where her father, Reverend C.L. Franklin, was minister. Gospel great Clara Ward was her strongest influence as a vocalist and Ruth Brown, with her string of rhythm and blues hits in the 1950s, headed her list of favorite secular singers. In 1957, after a few years in the church choir, a live recording of "Never Grow Old" was released on the local J-V-B gospel label, followed by a national distribution of the record on Checker. With a release of "Precious Lord" gaining notoriety in gospel circles, she began to think about pursing a career in the music business along the lines of what Sam Cooke, a friend of the family, had done, jumping the gospel ship onto the tempting shores of R&B and pop music.

Reverend Franklin was all for it, encouraging her to follow a career outside gospel music. There was a possibility of getting in on the ground floor with Berry Gordy's Tamla and Motown labels right there in her home town, but the opportunity to join the roster of the mighty Columbia Records proved irresisitible. Producer John Hammond, with more than 20 years' experience to that point, had already worked with literally dozens of great artists, among them Billie Holiday, another of Aretha's childhood favorites. Her early recordings under Hammond's guidance were outstanding jazz and R&B-styled pieces and were fairly successful, too. "Today I Sing the Blues," her first single, harnessed some of that gospel gleam she possessed and made it to the top ten of the R&B charts in a seemingly effortless move. "Won't Be Long," a hot, jazzy number (these first two hits featuring top-notch backing by the Ray Bryant Combo), proved she was a ball of energy, rising even higher in the top ten in early 1961 and making the pop charts too.

Those early singles seemed to have her running toward major stardom in a quick sprint, and it would have been interesting to see how her music might have progressed had she continued to work under Hammond's direction. But suddenly and without his approval, the label placed her with Robert Mersey, a producer and arranger with a proven pop music track record (Andy Williams, in fact, left Cadence Records for Columbia, beginning work with Mersey on a highly successful run of hit singles and albums at almost the exact time the producer took control of Aretha's session dates). The records that followed took a turn toward standards and even some really old-time stuff like "Rock-A-Bye Your Baby With a Dixie Melody," made famous in 1918 by Al Jolson (also a hit in 1956 by Jerry Lewis, which came off as a Jolson parody). If anyone at the label had doubts about the logic of this move, they dismissed them when the song became her first top 40 pop hit in November 1961. The flip side, "Operation Heartbreak," from a session produced that summer by Al Kasha (just before Mersey took over) put her in the R&B top ten for a third time, yet oddly there were no further collaborations with Kasha. Columbia, under the watchful eye of Mitch Miller, seemed determined to move her to what they felt was the next level, and that level veered away from a strict diet of rhythm, blues or jazz.

Her momentum slowed between 1962 and '64, but it wasn't necessarily a bad thing, although she once said she didn't feel Columbia was giving her the "big buildup" of Barbra Streisand and some of its other artists during that period. She had her share of misguided sessions, and some performances were uneven, but there were also recordings under Mersey's watch that are nothing short of incredible: "I Surrender, Dear," a ballad, recalls the essence of the great Dinah Washington (another influence) with that extra Aretha-oomph and a hot horn-riff hook. The flip side solidifies the 45 as an all-time great two-sider: "Rough Lover" has all the spunk, sass and sexual demanding anyone could imagine ('Now listen here girls, I'm gonna tell you what I want right now! I want a rough lover, I want a MAN!'). Both sides were inexplicably overlooked, charting very low. "Don't Cry, Baby" (Bessie Smith recorded the song in 1929 and it had been a hit for Etta James several months before Aretha took it on) shared a similar fate but is an equally compelling, even exciting, performance. "Try a Little Tenderness" and "Trouble in Mind" capped her 1962 output of singles. Both were standards with a vintage of 30 years or more; nevertheless they were pure wonders in the hands of Aretha. Listening to these songs should silence anyone overly critical of that first season spent with Robert Mersey.

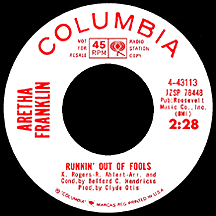

The next year was a different story. By mid-1963 she had dropped completely off the charts. Her music was gradually falling out of touch with current trends, even as singers like Streisand and Capitol's Nancy Wilson were stretching beyond the Broadway or jazz realms into a place where they could stay close to their roots and have hit records too. Aretha's frustration resulted in her showing up late or skipping sessions altogether. After several more months, the logical decision was made to let the soulful 22-year-old be soulful. Mersey even produced and arranged the uptempo "Soulville" in 1964, a solid fit, except that the definitive version had already been waxed by Dinah Washington a year earlier; at the same session, Aretha delivered one of her best efforts under Mersey's watch, the dripping-in-gospel gem "Lee Cross." Columbia made another sudden switch, reassigning Franklin to Clyde Otis, the former Mercury Records producer who, with arranger Belford Hendricks, had put Brook Benton on the map starting in 1959, revitalizing Washington's and Sarah Vaughan's careers along the way and breaking Timi Yuro at Liberty Records as a powerful early-'60s force. The soulful Miss Franklin had been, at least partially, in hiding; she was about to make her presence known.

As "Today I Sing the Blues" had been an important transition from gospel music to the larger rhythm and blues field, "Runnin' Out of Fools" was the turning point that put her on the soul track. One of her best singles on any label, it was her first to chart in a year and a half and almost became a hit in the fall of '64 with a mid-chart run topped only by "Rock-A-Bye Your Baby" three years earlier. Otis was at the helm of an impressive body of work after that, with a looser, more comfortable Aretha on minor 1965 sellers "Can't You Just See Me" and "One Step Ahead," Nick Ashford and Valerie Simpson's "Cry Like a Baby," and the Inez Foxx hit "Mockingbird," which with "Lee Cross" and others were released later in the decade after her career exploded. "Take a Look," penned and produced by Otis, was one of these, featuring Franklin's passionate delivery of a towering social message on a level with Sam Cooke's "A Change is Gonna Come" or labelmate Bob Dylan's "The Times They Are A-Changin'." Listening to the song now, it's a mystery why it wasn't a giant hit (ditto that sentiment on the Cooke and Dylan songs).

Legend has it that the master of ceremonies at a live show in 1965 gave Aretha a tiara and declared her "The Queen of Soul" (that would have happened while she was still at Columbia). Clyde Otis later said, "No one really knew what to do with her." But his statement wasn't entirely true. He knew. It's just that the company was unable to make it happen commercially. Yet you can't lay the blame on any particular person or on Columbia as a whole; timing may have had a lot to do with it. Still, during her years at the label with the many different approaches that were taken, Aretha was able to explore a variety of music not always available during her gospel upbringing in Detroit, which deepened her appreciation for all types of music, lending a depth to her later work lacking in many comparable singers' efforts. Starting with the Atlantic recordings in 1967, Aretha was at least one step ahead of and one level up from all the rest. Her natural talent had been obvious during her childhood in the 1950s; the experience at Columbia expanded her musical aptitude and was a necessary part of the progression that made her the great artist she was from 1967-on.

Enter Jerry Wexler. Aretha and Columbia had parted ways by 1966 and Atlantic Records was interested in her...and she in them. Yet they first offered her to the Stax label in Memphis (whose records Atlantic distributed), reasoning that they would know exactly how to bring out the best in her. So how do you figure Stax head Jim Stewart reacted? He passed! Atlantic signed the future "Lady Soul" and Wexler set about tapping into her most expressive, fiery traits. As part of his plan, he had her record the first single, Ronny Shannon's "I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You)," at the FAME studios in Muscle Shoals, Alabama with the Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section, the top musicians of the South's music hotbed - or anywhere, for that matter. It turned out to be her only session there. She was more comfortable recording in New York but continued working with the Muscle Shoals musicians, having them travel to her, instead of vice-versa, for all subsequently scheduled sessions.

The hits had immediate impact and kept coming, a new one every two months or so. Aretha became a sensation, playing piano on all the recordings as she had done very early at Columbia, but this time around she arranged the sessions, completely controlling the sound of the end product. "I Never Loved a Man" was her first top ten pop hit and a number one R&B smash in the spring of 1967. A major reworking of Otis Redding's 1965 hit "Respect" (with the addition of a lyrical reference to "Runnin' Out of Fools") was an across-the-board number one hit, an anthem of the late '60s, whether interpreted as a female empowerment message, civil rights statement or just plain sexy 'sock-it-to-me' dance number. Her sisters Erma ("Piece of My Heart") and Carolyn ("It's True I'm Gonna Miss You") were established professionals with their own label contracts by decade's end, often joing Aretha in the studio as backing singers (along with The Sweet Inspirations, who turned out several hits of their own for Atlantic, including "Sweet Inspiration").

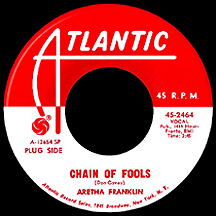

The public couldn't get enough of her in 1967 and '68: Shannon's "Baby I Love You," Gerry Goffin, Carole King and Wexler's poignant "(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman" and Don Covay's no-nonsense "Chain of Fools" were all fabulous, chart-dominating treats. Aretha and her husband Ted White contributed their own compositions, "(Sweet Sweet Baby) Since You've Been Gone" and "Think," to the legendary list as a full course of irrestible hits continued to be served up to perfection, the rousing "The House That Jack Built" and sensitive "I Say a Little Prayer" among them. Wexler wisely stood back (most of the time) and let Aretha Franklin do her thing. The potential that had been developed through trial and error at Columbia Records was realized in those early Atlantic recordings. And it was only the beginning of a long, triumphant reign for the Queen.

NOTABLE SINGLES:

- Never Grow Old - 1957

- Precious Lord, Part 1 - 1960

- Today I Sing the Blues - 1960

- Won't Be Long - 1961

- Rock-A-Bye Your Baby With a Dixie Melody /

Operation Heartbreak - 1961 - I Surrender, Dear /

Rough Lover - 1962 - Don't Cry, Baby - 1962

- Try a Little Tenderness /

Just For a Thrill - 1962 - Trouble in Mind - 1962

- Here's Where I Came In (Here's Where I Walk Out) /

Say it Isn't So - 1963 - Soulville - 1964

- Runnin' Out of Fools - 1964

- Can't You Just See Me - 1965

- One Step Ahead - 1965

- (No, No) I'm Losing You - 1965

- You Made Me Love You - 1965

- Cry Like a Baby - 1966

- I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You) /

Do Right Woman - Do Right Man - 1967 - Respect - 1967

- Lee Cross - 1967

- Baby I Love You - 1967

- Take a Look - 1967

- (You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman - 1967

- Mockingbird - 1967

- Chain of Fools - 1968

- (Sweet Sweet Baby) Since You've Been Gone /

Ain't No Way - 1968 - Think /

You Send Me - 1968 - The House That Jack Built /

I Say a Little Prayer - 1968 - See Saw /

My Song - 1968 - The Weight - 1969

- I Can't See Myself Leaving You - 1969

- Share Your Love With Me - 1969

- Eleanor Rigby - 1969

- Call Me - 1970

- Spirit in the Dark - 1970

- Don't Play That Song (You Lied) - 1970

- Border Song (Holy Moses) - 1970

- You're All I Need to Get By - 1971

- Bridge Over Troubled Water - 1971

- Spanish Harlem - 1971

- Rock Steady - 1971

- Day Dreaming - 1972

- All the King's Horses - 1972

- Angel - 1973

- Until You Come Back to Me (That's What I'm Gonna Do) - 1974

- I'm in Love - 1974

- Something He Can Feel - 1976

- Break it to Me Gently - 1977