BOBBY BLAND

When 15-year-old Robert Calvin Brooks moved with his family to Memphis in 1945, he had a decision to make. Coming from the nearby rural towns of Rosemark and Barretville with only a third grade education, he could either enroll in high school and attempt to make up for lost time or find work and try to achieve some measure of independence in the bigger city. Rather than face embarrassment in school, as his reading and writing skills were marginal, he chose the latter. No job was off-limits; for a time he delivered groceries and later he obtained a drivers' license and made better money parking cars, a somewhat prestigious position as most of his friends hadn't learned to drive. During this time he sang in gospel groups and plotted the path he would take in life. Singing won out...and we're all the better for it.

In 1950, his mother and stepfather opened a restaurant called the Sterling Grill, living in a space directly above. Robert worked washing dishes and clearing tables. He had begun hanging out on Beale Street and became good friends with Riley "B.B." King, a regular blues guitar player at some of the local hot spots. Changing his name to Robert Bland after his stepfather Leroy Bland, he and B.B., along with Rosco Gordon and Johnny Ace, performed together unofficially as The Beale Streeters, an outfit that at times included saxophonist Adolph "Billy" Duncan and drummer Earl Forest. He never attempted to learn a musical instrument, admitting that he had a problem concentrating on doing two things at once. So he focused on singing, basing his sound on idols Perry Como and Nat "King" Cole, odd choices for a fledgling blues vocalist. But with experience he developed a unique style, illustrating the sort of impressive results that can be achieved when a person specializes in just one thing.

WDIA, at AM 730 in Memphis, became a full time black-formatted radio station (the first of its kind) in 1948. The following year, B.B. King talked the station's owners into letting him host what began as a ten minute daily show, making him something of a local (and, soon after, regional) celebrity some three years before national stardom came with "Three O'Clock Blues," his first of several dozen hit records over an incredible four-decade span. All of the Beale Streeters began making records, apart from one another, around the same time. Gordon's "Booted" originated at the Sun Studio on Union Avenue; the master was licensed by owner Sam Phillips to Chess, then it was rerecorded for Modern. Both versions jointly reached the top of the rhythm and blues charts in early '52, knocking King's record from the summit! Little Junior Parker, another Beale Street musician who sometimes joined the others, landed his first hit, "Feelin' Good," on Sun the following year. Bland, whose first session took place at Sun in late 1951 with Gordon's band, waited longest for his taste of stardom. The results of that session, "Letter from a Trench in Korea" backed with "Crying," also licensed to Chess, struggled on release. Afterwards, four songs with backing by Ike Turner's band came out on a pair of Modern 78s but were largely ignored. For these early efforts he went by the name Robert Bland.

Memphis disc jockey Dave Mattis heard a few of the songs and was impressed, signing Bland as a solo artist to his newly-formed Duke Records. In 1952, "I.O.U. Blues" began what would be a 21 year run with the label, though success remained elusive for some time. Shortly after that first Duke release established his new stage name, Bobby "Blue" Bland, he joined the Army. During leave from his service he squeezed in a session or two, then returned for good in 1955 to a different situation: Mattis had sold Duke to Don Robey, top dog at Texas blues and gospel label Peacock. Robey ran both labels out of his Bronze Peacock Club, a hot night spot he'd opened in 1946 on Erastus Street in Houston's fifth ward, the city's African-American neighborhood. Bland began working with Bill Harvey, whose orchestra backed him on many recording dates in Houston. The band's trumpet player, Joe Scott, arranged those sessions and continued working with Bobby for more than a decade, supplying a key ingredient needed to ensure longevity in the music business: a signature sound, one that built itself on the blues while progressively flirting with a more mainstream, female-friendly brand of R&B.

For too long his records sold poorly, but he made a living chauffering for B.B. King and Junior Parker, his Beale Street buddies who had already made it big, occasionally peforming as an opening act for Parker. By 1957, with five years under his belt and no hits, his career seemed to have stalled. But he hung in there, and more importantly Duke Records also stayed the course, seeing potential in him to gain a following. After a few twists and turns, that following emerged and, by design, it was largely female. "Farther Up the Road" finally provided the long-awaited breakthrough in the summer of 1957. A fabulous blues number with distorted vocals, unusual in studio recordings but occasionally evident in Bland's finished takes, gave the recording a "live" feel. The revenge theme of 'Someone's gonna hurt you like you hurt me...further on up the road...baby you just wait and see' connected in a big way, going top ten R&B and crossing over into pop territory with a respectable mid-chart run.

A second hit came, after a couple of other singles, in late '58. "Little Boy Blue" had the singer playing a character in his own song: 'You used to call me Bobby...little boy blue...' Don Robey, who composed many of the great Bland tunes, began crediting himself as songwriter under the pseudonym Deadric Malone. "I'm Not Ashamed," again with those intriguingly distorted vocals, made an impact in the spring of '59. "Is it Real" featured flutes for the first, but not the last, time. As Bobby's vocals developed and matured, a higher-pitched howl he'd used from the beginning evolved into a raspy scream often referred to as his "squall," a trademark audiences came to expect whenever he performed.

As the '60s began, Bobby was hitting with every single he put out. His songs, usually written by Robey (as Malone), with help from other writers including Scott and Pearl Woods, usually spoke directly to women, who weren't exactly displeased with that approach or, for that matter, his appearance; expensive suits, flashy jewelry and a "conk" pompadour hairstyle aligned with the image his persuasive, pleading and/or scolding songs of love conveyed. In 1960 the "Blue" was dropped from his name on record labels as Robey sought to distance him from a blues image and move in a trendier R&B direction. With its piercing organ riff, "I'll Take Care of You," composed by Brook Benton, sounded very much like the blues but had a reassuring romantic quality and began a streak of seven consecutive top ten R&B hits. "Lead Me On" and its B side, "Hold Me Tenderly," utilized strings for the first time. "Cry, Cry, Cry" closed out his biggest year thus far. Bland's vocals on all were skillfully executed in a way that commanded the attention of his intended audience.

In March of '61 he topped all previous efforts with "I Pity the Fool" ('...who falls in love with you'), a scalding criticism of some anonymous woman ('Look at the people...I know you're wonderin' what they're doin'...they just standin' there...watchin' you make a fool of me!') and a number one hit on the R&B charts. Strong drumming and sax work highlighted the uptempo "Don't Cry No More," its smash follow-up. At about this time Bobby branched out from recording strictly in Houston with sessions in Chicago, Nashville and Los Angeles; in early '62 he made a crossover breakthrough, hitting the top 40 of the pop charts for the first time with the frantically-paced "Turn on Your Love Light," a wild mess of brass, guitars and piano with Bobby's squall at fever pitch; for many it remains the singer's definitive moment.

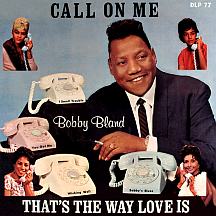

He toned things down with the foreboding "Who Will the Next Fool Be," a Charlie Rich song first waxed by the future "Silver Fox" the previous year. "Yield Not to Temptation" came off similar to "Turn on Your Love Light," adding manic female backing singers to outstanding effect. With "Stormy Monday Blues" (originally a hit in 1948 for T-Bone Walker as "Call it Stormy Monday But Tuesday is Just as Bad"), he revisited his roots and scored another hit. 1963 began with the two-sided "Call on Me" and "That's the Way Love Is," each hitting the top 40 separately while the B side reached number one R&B. Malone's songs burned both ends of the candle: "Sometimes you Gotta Cry a Little" brought Bobby closer to a mid-'60s soul vibe, while "The Feeling is Gone" wallowed strictly in the blues.

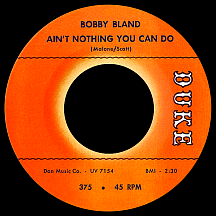

"Ain't Nothing You Can Do" compared the relative ease of controlling physical pain ('When you got a headache, a headache powder soothe the pain...') with the futility of curing a heartache; it was the blues brought soulfully into the mid-1960s, his biggest pop hit (and only one to reach the top 20). Next came a straightforward ballad, "Share Your Love With Me," followed by a tongue-in-cheek exercise in braggadocio, "Ain't Doing Too Bad" ('I've got a book full-a girls that I can call on the phone...they all dig me because my conversation is so strong!') Joe Scott's arrangements during these peak years were brass-heavy with prominent electric guitar that, with the blues-inspired lyrics of Malone and others, achieved a higher level of sophistication than most of the R&B acts of the day, apart from the phenomenal Ray Charles and, perhaps, a few others. Under Scott's direction, the Bland band had its own style, if only a tad to one side of Charles or to the other of Quincy Jones, yet it was instantly recognizable in most instances; a mix of brass, guitar, bass, piano and drums with a sound that oozed "Blue."

The mid 1960s found Bland and company further seduced by the modern soul movement. Highlights from this time include "These Hands (Small But Mighty)" and "I'm Too Far Gone (To Turn Around)" in '65, "Good Time Charlie" and "Poverty" in '66, "You're All I Need" in '67 and a smoky updating of Joe Turner's benchmark '51 hit "Chains of Love" to close out the decade. Bobby had been drinking heavily, a habit he picked up while in the Army a decade earlier. By the late 1960s it became more than a minor annoyance for those around him and Scott, for one, reached a point where he didn't want to associate with the singer any longer. For the next few years, Bobby worked with a number of different producers and arrangers and his work suffered somewhat. Around 1971 he turned things around; off the bottle for good, the quality of his music became noticeably stronger.

Don Robey sold his Duke and Peacock labels to ABC Records in 1973. Bland stayed with the company (appearing first on Dunhill, then later on the ABC label, and finally on MCA starting in '79), enjoying a resurgence in popularity with some of the biggest hits of his career, including "This Time I'm Gone For Good" in '73 and "I Wouldn't Treat a Dog (The Way You Treated Me)" in '75. He collaborated with Beale Street buddy B.B. King on a couple of albums and the pair clicked with "Let the Good Times Roll," a hit in '76. They toured together for many years afterwards. In 1985, Bobby Bland signed with the Mississippi-based Malaco Records, a company that specialized in recording classic blues, soul and gospel acts. He stayed with the label throughout the remainder of his impressively productive 83 years.

NOTABLE SINGLES:

- I.O.U. Blues - 1952

- I Woke Up Screaming - 1955

- I Smell Trouble - 1957

- Farther Up the Road - 1957

- Bobby's Blues - 1958

- Little Boy Blue - 1958

- I'm Not Ashamed - 1959

- Is it Real - 1959

- I'll Take Care of You - 1960

- Lead Me On - 1960

- Cry Cry Cry - 1960

- I Pity the Fool - 1961

- Don't Cry No More - 1961

- Turn on Your Love Light - 1962

- Ain't That Loving You - 1962

- Who Will the Next Fool Be - 1962

- Yield Not to Temptation - 1962

- Stormy Monday Blues - 1962

- Call on Me /

That's the Way Love Is - 1963 - Sometimes You Gotta Cry a Little - 1963

- The Feeling is Gone /

I Can't Stop Singing - 1963 - Ain't Nothing You Can Do - 1964

- Share Your Love With Me /

After it's Too Late - 1964 - Ain't Doing Too Bad - 1964

- Black Night /

Blind Man - 1965 - Ain't No Telling /

Dust Got in Daddy's Eyes - 1965 - These Hands (Small But Mighty) - 1965

- I'm Too Far Gone (To Turn Around) - 1966

- Good Time Charlie - 1966

- Poverty - 1966

- Back in the Same Old Bag Again - 1966

- You're All I Need - 1967

- That Did It - 1967

- Driftin' Blues - 1968

- Rockin' in the Same Old Boat - 1968

- Gotta Get to Know You - 1969

- Chains of Love - 1969

- If You've Got a Heart - 1970

- Keep on Loving Me (You'll See the Change) - 1970

- Do What You Set Out to Do - 1972

- This Time I'm Gone For Good - 1973

- Goin' Down Slow - 1974

- Ain't No Love in the Heart of the City - 1974

- I Wouldn't Treat a Dog (The Way You Treated Me) - 1974

- Yolanda - 1975

- Let the Good Times Roll - 1976

with B.B. King - The Soul of a Man - 1977

- Love to See You Smile - 1978