SANFORD CLARK

The Fool

Although he was the son of a wildcat oil driller, Lee Hazlewood didn't make his fortune off dad's precarious line of work (the highly volatile wildcat business often involves drilling on potentially oilless land). Instead he forged a hit-and-miss career in music; the disc jockey-songwriter-producer-singer had a great deal of success with "twangy" guitar man Duane Eddy in the late '50s and early '60s, then reached another peak a few years later working with the likes of Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin at Frank's Reprise label. He became something of a household name after the pleasurable experience of writing and producing hits for Nancy Sinatra led to a four-pronged series of hit duets with the "Boots" girl that, to anyone who hadn't heard him sing (which would be...practically everyone), revealed a deep, western-movie-like baritone. Maybe this level of stardom would never have been reached if, years before, he hadn't taken a chance and made a record with hesitant rock and roller Sanford Clark.

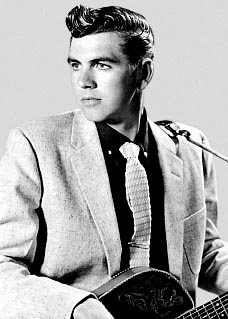

Phoenix, Arizona had been Clark's home since early childhood. He started playing guitar around age eleven and worked part time in construction during his teens, studied commercial art at Phoenix Tech, entered the R.O.T.C. program and served in the Air Force, during which time he was stationed on Johnston Island (nuclear bombs were tested near there a few years later), where he formed a band that won a talent contest 950 miles away in Hawaii. After such an adventurous phase he returned to Phoenix and started performing in area clubs. Guitarist Al Casey, a friend from his school days, managed to get Hazlewood, a deejay at KTYL in nearby Mesa, to check him out. The two made a connection; Lee was from Mannford, Oklahoma, not far from where Sanford was born.

Clark was nervous about the propect of stardom, but Hazlewood paid for session time at Floyd Ramsey's recording studio in Phoenix anyway. In March 1956, two songs were completed by a quartet cobbled together to back the singer. Axe man Al played lead and his wife, Corky Casey, took the rhythm guitar spot, while two of the Ramster's associates, bassist Jimmy Wilcox and drummer Connie Conway, rounded out the group. "The Fool" ('...a crazy fool...who told...his baby...goodbye'), a Hazlewood composition credited to wife Naomi Ford, was the more impressive of the two tracks. Casey supplied an adjusted version, in a slightly higher key, of the guitar riff from a current hit, Howlin' Wolf's "Smake Stack Lightning." A reverb effect enhanced Conway's beat, accomplished by pounding on a drum case. Clark's upfront vocal fit the folky ballad about a romantic misstep; Hazlewood achieved an echo sound in the small studio similar to what Sam Phillips had done at Sun in Memphis, yet the end result was pretty unique for its time.

Ramsey issued the sides on his MCI label and "The Fool" got enough action locally that Randy Wood of Dot Records (who'd recently moved his operation from Gallatin, Tennessee to Hollywood, California) showed interest and nabbed the master for wide release. Al's guitar contribution, by the way, was noted on both MCI and Dot labels, kind of a "you-did-good" perk-without-extra-pay from Lee. Bill Randle, a top-rated personality on WERE in Cleveland, played the record early and often, helping to break it nationally. Onstage, Clark kept gyrations of the Elvis-and-other-rockers variety to a minimum. Randle gave him the nickname "Sandy"...but the unpretentious singer nixed that idea. The summer single flew up the charts, facing mild competition from a cover on Jubilee by New Jersey pop group The Gallahads, but it was Clark, also relocated to Hollywood, who spent a good chunk of September and October in Billboard's top ten. Hazlewood began preparing what must certainly be the next major hit.

"A Cheat" (composed by Naomi and Lee...though weren't they sorta like the same person?) had a similar if slightly more eerie sound; it stalled after a few weeks on the charts in December. Touring with the likes of Gene Vincent and Carl Perkins absorbed most of Sanford's time. He made a screen test for Universal International, but nothing came of it. An agreeable remake of Merle "Sixteen Tons" Travis's "9 Lb. Hammer" appeared in the Cash Box top 50 in early 1957. Wood decided to try positioning Clark in a balladeer role similar to his biggest act (by far), Pat Boone, which resulted in a lackluster remake of "Darling Dear," The Counts' R&B hit on Dot from 1954. Uptempo rocker "Lou Be Doo" delivered the goods while "The Man Who Made an Angel Cry" retained a bit of the "Fool" feel, but nothing connected sales-wise.

After "Modern Romance," a frantic shoulda-been-a-hit shuffler penned by Dot artist and underrated rocker Danny Wolfe, Hazlewood took the Clarkster to Jamie Records, where Duane Eddy had just started "Moovin' n' Groovin'" towards stardom. They headed back to Phoenix and Ramsey's Audio Recorders; Casey came along for the ride and before long was touring with the twangmeister, who played guitar on Sanford's first Jamie single, "Still As the Night" ('...cold as the wind...don't guess I'll see...my baby again'), another variation on "The Fool" that spent a solitary week on the Cash Box chart in September of '58. The Jamie masters, all produced by Lester Sill and Hazlewood, utilized a few new tricks; late-'59's "Son-Of-A-Gun" had a C&W lean and the early '60 single "Go on Home" seemed to be trying too hard to emulate the western tales popular at the time by the likes of Marty Robbins and Johnny Cash. Clark left Jamie that spring and managed only a couple of record releases, on the Project and Trey labels, over the next couple of years.

Al Casey finally managed a few chart hits in '62 and '63, the infectious guitar-star mimicry of "Surfin' Hootenanny" foremost among them. Hazlewood went to work for Warner Bros. in the mid-'60s and gave it another go with Clark; "Houston" showed promise, but Lee also produced a version by "Little Ole Wine Drinker" Dino for Warner's Reprise imprint that eclipsed Clark's original. Returning to Phoenix yet again, he remade "The Fool" for Ramco (Ramsey's mostly-country concern) with future star Waylon Jennings and Donnie "Need You" Owens producing. The rockabilly strain of the early productions was gone, replaced by a style aiming for country success; "Shades" and "It's Nothing to Me" were compelling (the latter penned by Leon Payne and first recorded by Arizonan Loy Clingman in 1957, by '64 it had morphed into an R&B novelty, "T'ain't Nothin' to Me" by The Coasters), while "(They Call Me) Country" made clear Clark's (moreso Ramsey's?) intentions.

Rejoining Hazlewood in 1967 and signing with his new LHI Records, Clark put out one single during each of the next three years. Dallas Frazier's "The Son of Hickory Holler's Tramp" was a hit...just not for Sanford. O.C. Smith covered the song in early 1968 and it kicked off a late-'60s string of hits that made up for more than a decade of bad breaks. Clark had been overlooked, cut off at the pass or just plain rejected throughout his own post-hit decade-plus of attempts. But "The Fool" will not be forgotten, if only for the fact "The Big E" included his version on the 1971 album Elvis Country. Lee's/Naomi's song is an early rock classic; its artist, Sanford Clark, not so much, at least not with the public at large. Soured on the highly competitive music industry and its built-in challenges, his "backup plan" kicked in at some point in the 1970s (though he has since done some performing and recorded a song or two). He returned to his birthplace, Tulsa, and set to the task of making an honest living in construction.