THE DRIFTERS

From the outside looking in, The Drifters ranked among the greatest vocal groups in music history, with many of the best and most memorable recordings of the 1950s and 1960s. On the inside it was quite nearly the opposite, one of the worst conceivable situations of mismanagement and chaos, with literally of dozens of singers joining, leaving, some joining again, then leaving again, unappreciated at almost every turn. It's a wonder how such a wealth of outstanding music came out of these circumstances.

One thing's for certain: there was no lack of talent where this group was concerned, in spite of the heavy-handed management style of George Treadwell. A former jazz trumpet player, Treadwell was Sarah Vaughan's manager (and husband from 1946 to 1958), key in shaping Sarah's image, exposing her beyond jazz circles and into the mainstream during the '50s. When he became the Drifters' manager in 1953, he treated the vocalists as though they were a minor part of his operation, paying them minimal wages (usually around a hundred dollars a week) while demanding long hours from each, recording and touring while sharing little in the riches that came from the top-selling records and headlining engagements that were consistent for more than a dozen years. As a result, many members became disenchanted, sometimes quitting the group, other times being fired by Treadwell for no reason other asking for a raise! Personnel changes became the norm, a constantly swinging door with one unhappy singer leaving as a new one willing to give it a shot would come in. Some have said that the group was named because members kept drifting in and out, but it more likely developed as a bitter joke deriving from the discord experienced by many of what would be at least 50 different Drifters singers throughout the years.

The Drifters name was a big part of the Atlantic Records roster from 1953 to 1972. While the group's history was being made over those 19 years, as well as in the post-Atlantic era, they went through six distinct phases, each with varying configurations of top rate producers, writers and musicians, featuring lead singers with a style and verve that set them apart from the others. You could say they were six different acts under the same name, with literally hundreds of interchangeable parts adding up to an impressive collection of musical output.

Clyde McPhatter was becoming increasingly dissatisfied with his role in the success of The Dominoes. A member since its inception in 1950 (billed at first as Clyde Ward), McPhatter had been a major part of a continuous string of hits including the R&B number ones "Sixty Minute Man" in 1951 and "Have Mercy Baby," showcasing his lead vocals, in 1952. The group's leader, Billy Ward, ran operations much in the way that Treadwell later would with the Drifters, keeping his singers on a modest weekly salary. Atlantic president Ahmet Ertegun, a Dominoes fan, caught one of their shows at New York City's famous Birdland nightclub and noticed Clyde wasn't present. Confirming with Ward that McPhatter had left the group, he arranged to have him join Atlantic with the plan that he would front his own backing group, calling them Clyde McPhatter and the Drifters.

At about this time former music writer Jerry Wexler was hired for what would be a long and important tenure as a producer for the label. At first it was a challenge putting an acceptable vocal team together, as they auditioned several of Clyde's friends, some members of gospel group The Mount Lebanon Singers, whom he'd performed with early in his career. None of them were up to Ertegun's or Wexler's standards, but a lineup was finally put in place with gospel singers Bill Pinckney and brothers Gerhart and Andrew Thrasher, in addition to Willie Ferbee and guitarist Walter Adams. With Clyde singing lead they recorded the first single, Jesse Stone's somewhat humorous commentary on the relationship between love and finances, "Money Honey," a long-running number one R&B hit in late 1953 on a level with the earlier Dominoes chart-toppers. It also became one of the key records in rock and roll's development; Elvis Presley waxed his own well-received version during his first sessions with RCA Victor in January 1956.

Members started coming and going almost immediately, and one move within the ranks was notable: Bill Pinckney, hired as a baritone, became the group's bass vocalist. A two-sided hit followed: "Such a Night" (written by Lincoln Chase) and McPhatter's own composition "Lucille." Next up was a song written by McPhatter and Wexler, "Honey Love," banned by a number of stations due to its suggestive 'I need it in the middle of the night' lyrics; so naturally it became the group's second number one hit in July '54. Another off-color suggestion followed with the next hit, "Bip Bam" ('...thank you, ma'am!'), after which the group did a 180 with Irving Berlin's classic "White Christmas" featuring Pinckney's bass vocal as the lead, this version becoming a seasonal standard in its own right. After "What'cha Gonna Do" (which has been credited with inspiring Hank Ballard when he wrote "The Twist" a few years later), Clyde was drafted and stationed in Buffalo, New York. As far back as "Honey Love" he had let it be known he wanted a solo career (at which time label credits began listing his name below that of the group) and eventually Atlantic was more than happy to accommodate, having the Drifters continue separately. Without considering the effect it might have on the other singers, McPhatter sold his interest in the act to Treadwell, giving the manager complete control.

With McPhatter gone, the second phase of The Drifters had less direction but soon took on a life of its own. "Little Dave" Baughn, who sounded similar to McPhatter, was hired but proved difficult to work with and was replaced by Pinckney discovery Johnny Moore of Cleveland group The Hornets. Moore's lead on the Buck Ram song "Adorable" and Pinkney's tenor lead on its flip side, "Steamboat" (written by Buddy Lucas), landed both songs in the R&B top ten in late 1955. Ertegun then gave Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller a shot at writing for and shortly thereafter producing the group; while not as successful with the Drifters as they ultimately would be in masterminding The Coasters' successful run, the group's sound became more mainstream and thus a bit closer to what would someday translate to greater success reaching a wider audience.

Moore sang lead on some excellent singles: "Ruby Baby" (later a hit for Dion in 1963) and "I Gotta Get Myself a Woman" in 1956, then "Fools Fall in Love" the following year, the first of the group's releases to cross over to the pop charts. He received his draft notice about this time and Pinckney quit in a dispute with Treadwell over salary. They were replaced by Bobby Hendricks (a member of The Swallows during that group's leaner years), who delivered an energetic lead vocal on "Drip Drop," another great Leiber-Stoller production (and another hit for Dion in '63). Hendricks left after a short time, though, enjoying a big solo hit on the Sue label, "Itchy Twitchy Feeling," hitting the charts at the same time as his Drifters single in the summer of 1958.

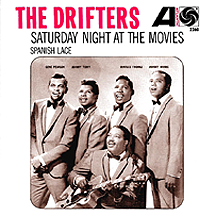

Lacking an acceptable candidate to sing lead, the remaining members suddenly found themselves working harder trying to keep the group going at a reasonable professional level. When they approached Treadwell for more money, his temper ran short and he fired them all. It appeared The Drifters had come to an end. Ertegun and the other Atlantic executives felt the name still had commercial potential, and of course their manager (who had a one-year contract for them to appear at the Apollo Theater) was anxious to continue making money from the group, particularly since his divorce from Sarah Vaughan, stalling their business dealings as well, happened at about the same time. He approached Lover Patterson, manager of The Five Crowns, about hiring them to fulfill the group's performance obligations, and so started phase three, a complete break from the first two. They made the deal (with Patterson relegated to a position as road manager), but things didn't go smoothly with audiences, since this group wasn't anything close to the act they had paid to see. The Five Crowns, consisting of Benjamin Earl Nelson (soon after changing his professional name to Ben E. King), Dock Green, Charlie Thomas and Elsbeary Hobbs, took the obvious next step (minus fifth Crown James Clark) and went into the studio to record as The Drifters with Leiber and Stoller at the helm.

By early 1959, the use of strings on rhythm and blues recordings had become somewhat of a trend, successfully utilized on hits by The Platters, Brook Benton, Jesse Belvin and others. For the first "new Drifters" single, Leiber and Stoller decided to use a string section arranged by Stan Applebaum on a Ben E. King song (who shared writer credit on the label with Patterson and Treadwell), "There Goes My Baby." Applebaum's swirling strings were prominent on the recording and King's vocals were drenched in reverb unheard of for the time. Jerry Wexler, for one, thought it was terrible effort, saying it sounded like two different radio stations tuned in at the same time. The song was so unlike anything that had come before that it connected with the public, becoming a monster hit: number one R&B and a breakthrough on the pop charts, going as high as number two.

The latest version of the group was off and running, with the follow-up hits "(If You Cry) True Love, True Love" (the first of many of their hits written by Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman, featuring a lead vocal by yet another new singer, Johnny Williams) and more great Ben E. King-led classics also written by the Pomus-Shuman team: "Dance With Me," "This Magic Moment" and "Lonely Winds." With all this success, though, King quickly tired of the substandard hundred-dollars-a-week from Treadwell that all the earlier Drifters had had to deal with and decided, like McPhatter, Hendricks and others before him, to try his hand at a solo career, though he stuck around for awhile to sing lead on a few more of the group's singles.

The former Five Crowns' crowning moment came in the fall of 1960. Shuman had developed an interest in Spanish rhythms after a trip to Europe, and with Pomus wrote "Save the Last Dance For Me." The production had a style and rhythm previously uncommon for an American R&B/pop song that would be imitated on quite a few records into the following year. The label was unsure of the potential for the song, promoting the more mainstream-sounding "Nobody But Me" as the A-side, but ultimately it was "Last Dance" that scored, hitting number one on the R&B and pop charts in October and November of 1960, the biggest Drifters hit ever.

King made his departure in early 1961, moving to the company's subsidiary label Atco, and after one last hit with him on lead, Pomus and Shuman's "I Count the Tears," the fourth phase of the ongoing Drifters legacy was under way. Continuing to draw from gospel influences, they quickly found a replacement in Rudy Lewis of The Clara Ward Singers. Rudy had a strong, confident sound, and his recordings for the group were among their best. His rookie assignment was also the first of the group's singles written by Gerry Goffin and Carole King, one of the top teams working out of New York's Brill Building. "Some Kind of Wonderful" was followed by "Please Stay" with Rudy again on lead, a song written by Burt Bacharach and Bob Hilliard (Bacharach discovered Dionne Warwick singing backup on a Drifters session; at Scepter Records he later worked with her on an unprecedented string of hits).

In late '61 and early 1962, Charlie Thomas, in the background the previous three years, took over lead vocal duties on the next three singles: the Pomus-Shuman compositions "Sweets For My Sweet" and "Room Full of Tears" in addition to Goffin and King's "When My Little Girl is Smiling." Lewis returned as lead with the escapism-message song "Up On the Roof," a Goffin-King classic and one of the group's biggest hits. The very next single with Lewis wasn't a slouch, either: "On Broadway," a song about the difficulty of breaking into the business, played like a Brill Building biography. Written by Cynthia Weil and Barry Mann (their first outing on a Drifters song) along with Leiber and Stoller, it also featured a funky, twangy guitar solo by Phil Spector, then at his creative and commercial peak with the Philles label, clearly taking a break from running this own company and having a little fun. The song followed the previous top ten hit back into the winners' circle.

Johnny Moore returned to the lineup in 1963 after his tour of duty and a failed attempt at a solo career. Phase five began for the group when Bert Berns (also known as Bert Russell on songwriting credits) took over as producer at that time, often working with arranger Teacho Wilshire. It took a tragedy the following spring to define the group's latest juncture: Rudy Lewis was scheduled for a recording session with the group in May, but died the night before in his hotel room. Reports on what exactly happened ranged from his drinking heavily to choking from overeating to Wexler's account of death from a heroin overdose. The session went on as scheduled with Moore stepping up to handle the lead vocal on "Under the Boardwalk." Written by Arthur Resnick and Kenny Young, the song became another top ten hit and with the next single by the same writing team, "I've Got Sand in My Shoes," the Drifters were thereafter strongly associated with the Carolina "beach" music scene.

Moore's second stint with the group proved to be a lasting one; after another hit at the end of 1964, Mann and Weil's "Saturday Night at the Movies," he remained lead singer throughout the rest of the act's years with Atlantic. With George Treadwell's death in 1967, monetary concerns lessened, but there were no more hits by that time and the group was primarily existing on the road while enjoying the luxury of making records into the early 1970s. At the end of the group's long-running contract with Atlantic in 1972, the sixth phase began for the act when Moore found a market for their music in England. With a mostly-new lineup of backup singers, he scored several big hits under the Drifters name between 1973 and '76 (one of these, "Kissin' in the Back Row of the Movies," had a brief appearance on the R&B charts in America).

To sum things up, it may have been a stressful, frustrating experience for many of the group's principal players, but in the bigger picture they created an exciting, seemingly nonstop party for the fans, of which I consider myself a longstanding member. And it wasn't a total loss for everyone involved: Clyde McPhatter extended his success with The Dominoes and The Drifters into a solo career with classic hits like "Treasure of Love," "A Lover's Question" and "Lover Please." Ben E. King stands firmly in the pop culture consciousness with "Spanish Harlem" and the huge success of "Stand By Me." And, in spite of many barely-connected touring versions of mock-Drifters groups, Johnny Moore kept the original Drifters lineage alive for more than three decades after the group's heyday.

NOTABLE SINGLES:

- Money Honey - 1953

as Clyde McPhatter and the Drifters - Such a Night - 1954

as Clyde McPhatter and the Drifters / - Lucille - 1954

as Clyde McPhatter and the Drifters - Honey Love - 1954

as the Drifters featuring Clyde McPhatter - Bip Bam - 1954

as the Drifters featuring Clyde McPhatter - White Christmas - 1954

as the Drifters featuring Clyde McPhatter and Bill Pinckney - What'cha Gonna Do - 1955

as Clyde McPhatter and the Drifters - Adorable /

Steamboat - 1955 - Ruby Baby - 1956

- I Gotta Get Myself a Woman /

Soldier of Fortune - 1956 - Fools Fall in Love - 1957

- Hypnotized - 1958

- Drip Drop /

Moonlight Bay - 1958 - There Goes My Baby /

Oh My Love - 1959 - Dance With Me /

(If You Cry) True Love, True Love - 1959 - This Magic Moment /

Baltimore - 1960 - Lonely Winds - 1960

- Save the Last Dance For Me /

Nobody But Me - 1960 - I Count the Tears - 1961

- Some Kind of Wonderful - 1961

- Please Stay - 1961

- Sweets For My Sweet - 1961

- Room Full of Tears - 1961

- When My Little Girl is Smiling /

Mexican Divorce - 1962 - Stranger on the Shore - 1962

- Up On the Roof - 1962

- On Broadway - 1963

- Rat Race /

If You Don't Come Back - 1963 - I'll Take You Home - 1963

- Vaya Con Dios - 1964

- One Way Love - 1964

- Under the Boardwalk - 1964

- I've Got Sand in My Shoes /

He's Just a Playboy - 1964 - Saturday Night at the Movies - 1964

- At the Club - 1965

- Come On Over to My Place /

Chains of Love - 1965 - Follow Me - 1965

- I'll Take You Where the Music's Playing - 1965

- Memories Are Made of This - 1966

- You Can't Love Them All - 1966

- Baby What I Mean - 1966

- Ain't It the Truth - 1967

- Still Burning in My Heart - 1968

- Kissin' in the Back Row of the Movies - 1974