EDDIE HARRIS

Exodus

1961 was the year of Exodus. Not the second book of the Bible, mind you, but the movie adaptation of Leon Uris's 1958 novel based on the Arab-Israeli war that had begun a decade earlier. Dalton Trumbo adapted the screenplay from the book and Otto Preminger directed the epic production, which premiered in December 1960 and starred Paul Newman, Eva Marie Saint and Sal Mineo, the latter earning an Oscar nomination for Best Supporting Actor for his performance. As good as the film is, and it was one of 1961's top-grossing box office hits, I would argue that the dynamic Oscar- and Grammy-winning music score by Ernest Gold is its strongest feature.

Dual piano partners Ferrante and Teicher unleashed a massively popular cover version of the "Exodus" title theme in November, more than a month before the movie's release, and Mantovani's version, arranged in a classical style more serious in nature than the Italian orchestra leader's signature work, appeared at about the same time, ensuring that many people would be familiar with the theme music before having a chance to witness the widescreen film or even buy a copy of Gold's soundtrack (released to coincide with the movie, it ultimately leapt to number one on the album charts in time to hold Mantovani Plays Music from Exodus and Other Great Themes at number two). Ferrante and Teicher's hit, top ten on the charts from December '60 through February '61 and a million seller, became the definitive recording of the song for millions of people, though even more versions came in its wake. Pat Boone penned lyrics for the instrumental (his single issued under the title "The Exodus Song (This Land is Mine)") and Édith Piaf sang a different set of lyrics in French (translated as 'They found the land of love'). And then there was the jazz saxophone interpretation by Eddie Harris that took the masterful theme and turned it on its ear.

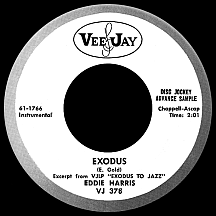

Chicago-born Harris started out playing piano, then later developed an interest in the vibraphone. Not limiting himself to percussive instruments, he picked up a tenor sax during his teens and it became his primary focus. His first professional job came in the mid-'50s when he briefly played piano backing saxophonist Gene Ammons. After serving a term in the Army, he moved to New York and worked primarily as a pianist, though gigs were scarce. Returning home in 1960, he was signed by Vee-Jay, surprising label owners Vivian Carter and James Bracken, and most everyone else, when he played tenor sax on every track on his first album, Exodus to Jazz, leaving the 88 keys in the capable hands of Willie Pickens. The title track, an extraordinary six-and-a-half minute opus quite unlike the dramatic intensity of the previous pop versions, was edited to two minutes for release on a 45 (identified on the label as an "excerpt") and reached the top 40 in June, whetting music lovers' appetites for the full LP, which spent most of the summer among the top ten albums, peaking at number two in August beneath Something for Everybody by Elvis Presley (and a few notches above Gold's long-running Exodus soundtrack).

With a million-seller under his belt, Harris had carte blanche to do anything that satisfied his creative urge. He made six more albums for Vee-Jay over the next couple of years that featured a cross-section of original songs, vintage selections and currently popular movie themes (in the hopes of repeating his one cinematic-inspired success), sticking with his sax throughout. 1962's Eddie Harris Goes to the Movies featured his take on "Tonight" from West Side Story and nine vintage film themes, eschewing the jazz combo for lush orchestral backing by Dick Marsh; critics scoffed at the shameless maneuver, a theoretic no-no for any "serious" jazz artist. In some ways I agree, preferring his early-'63 Bossa Nova LP that features Eddie's self-penned "Lolita Marie."

In 1964 and '65 Eddie made three albums for Columbia, where he was promoted as the "Cool Sax" guy. After that he signed a long-term deal with Atlantic Records and began breaking out of the formula he'd established at Vee-Jay. The In Sound took a more progressive approach with its standout track "Freedom Jazz Dance" and for the 1966 longplay Mean Greens he set the saxophone aside to play some down-and-dirty electric piano on "Listen Here," the first version of a tune he'd written that would later become a hit. Experimentation came into play during these years; Harris connected his sax to a Varitone processor (a filter typically used on guitars) to get unusual effects. The "varitone sax" was featured on his fourth Atlantic album, The Electrifying Eddie Harris, and used to great effect on the second rendition of "Listen Here," a hit in the summer of 1968 on pop and R&B charts; the album landed him a Grammy nomination in the category Best Instrumental Jazz Performance by a Small Group or Soloist with a Small Group.

Plug Me In and the single "It's Crazy" displayed some wild sax/varitone sax handling with arrangements ahead of the fusion curve that became the jazz-rock rage in the 1970s. Eddie created his own oddball instrument he called the saxobone, a sax with a trumpet mouthpiece (and its obvious counterpart, a trumpet with a sax mouthpiece), in his ongoing quest to create new sounds. In June 1969 he and pianist Les McCann joined forces onstage at the third Montreux, Switzerland Jazz Festival, catching a hot groove with singer-songwriter Gene McDaniels' "Compared to What," McCann doing vocal duty (he rhymes '...that stinking mutt' with '...what'!), from their 1970 single and album Swiss Movement, which scored a Grammy nom in the same Instrumental Jazz category as before.

Later projects for Atlantic included E.H. in the U.K., recorded in England in 1973 with Steve Winwood on piano, Jeff Beck on guitar and several other Brit rockers. "Is it In" had a strong groove and was a mildly popular single in 1974. Eddie had been doing monologues, often off-color, for some time; in a bizarre development, Atlantic issued a full album of these comedy routines in 1975, titled The Reason Why I'm Talking S--t. Had he gone too far? Or was it just another example of the many facets of Eddie Harris? He left Atlantic soon afterwards, but recorded and performed prolifically until his death in 1996 at age 62. His final "Exodus," sad to say, came too soon.