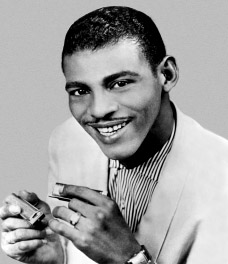

LITTLE WALTER

The harmonica isn't usually considered a lead instrument in a band, though with the rise of the blues in the pre- and post-World War II era its use became more prominent. Players like Sonny Terry (who developed his style as a teenager in the 1920s), Sonny Boy Williamson (born John Lee Curtis Williamson, his career began in the mid-'30s) and a few others had a profound influence on the genre. By the time Little Walter reached his peak in the '50s, listeners were ready for a more aggressive sound and Walter, who'd been experimenting with his technique since childhood, addressed that desire.

Alexandria, located roughly in the middle of the state of Louisiana, was the birthplace of Marion Walter Jacobs, born in 1930 and drawn to music at a very young age. He started practicing on a cheap harmonica around age six, about two years before his family moved northward to Chicago. Within a few years he was working for a grocery store as a delivery boy, carrying his harmonica with him, always ready to play a tune: waltzes and polkas he'd been exposed to by the older folks and pop songs he knew from the radio. The blues gradually soaked in. Eventually it became his entire focus.

The Maxwell Street Market on Chicago's West Side was an area where people from all types of ethnic backgrounds lived, worked and traded. Set up in an area covering about a half mile, it was something more than a mere flea market, serving for decades as a meeting place where anyone could wheel and deal for items large or small. Businessmen and impromptu sellers coexisted with street performers, amateur and semi-professional, playing for tips; bluesmen, gospel and pop singers, comedy and novelty acts were regularly seen. By the time he entered his teens, Marion was a regular at what might be considered a lower-class social hub. Soon he obtained the name Little Walter, the market regulars supplying the "Little" part while he preferred his middle name.

Walter's efforts to get a foot in various nightclub doors didn't happen right away because of his age. As local bluesmen became aware of his raw talent, opportunities resulted. At some point he picked up a guitar and was pretty good at that, too. By age 15 the chance to impress clubgoers became reality; he built a friendship with transplanted Mississippian Big Bill Broonzy. Memphis Slim and Tampa Red, both Chicago nightclub regulars despite their outside-the-region names, were also agreeable to having Walter join them from time to time. In 1946 he made his first record, "Ora-Nelle Blues," for a short-lived local label, Ora Nelle. Billed as Little Walter J. (with Othum Brown on guitar), the track revealed an anguished vocal sound as strong as many seasoned blues singers.

Semi-regular Maxwell Street bluesmen Jimmy Rogers and Muddy Waters (real name: McKinley Morganfield) quickly became aware of Walter's talents and occasionally performed with him. More recordings for Chicago-based labels were made in 1950 by the Little Walter Trio (a studio configuration that didn't necessarily include a set group of musicians); "Muskadine Blues" on Regal and "Just Keep Lovin' Her" on Parkway (a remake of an earlier Ora Nelle tune with a slightly different title) had decent vocals and strong Sonny Boy-style harmonica breaks. Waters, who was signed to Chicago's Aristocrat label, brought Little Walter into the studio in 1950, at about the time Aristocrat became known as Chess Records, to play on songs like "Louisiana Blues," Waters' first national R&B hit to feature Walter's harmonica technique.

As Muddy Waters' career took off in the early '50s, Little Walter maintained a steady presence, blowing his harp on "Long Distance Call" and "She Moves Me" and making a rare switch to guitar for "Honey Bee" and "Still a Fool," all of these recordings reaching the top ten of the rhythm and blues Best Sellers and/or Juke Box rankings in Billboard magazine. In 1951, hoping to better compete with the louder, more prominent guitars on Muddy's sessions, he tried something new. Plugging a small microphone into an amplifier, he held it in his hands to get a stronger sound, a trick that had been done by others. Cranking the levels as far as possible, he achieved a degree of distortion but also tonal effects that were unlike what had previously been reached. The first Waters track to demonstrate this approach was "Country Boy," recorded in the summer of '51 but not issued until spring '52. Label owner Leonard Chess then booked Little Walter for his very own recording session.

An instrumental tune he'd called "Your Cat Will Play" received the amplified harp treatment near the end of a May 1952 Waters session with backing by Muddy and Jimmy Rogers on guitar and Elgin Evans on drums. The title was changed to the simpler "Juke" and credited to Little Walter and his Night Cats. The catchy midtempo jam, released on Chess Records' Checker subsidiary, reached number one on the national R&B chart the final week in September. Afterwards, Little Walter prioritized his own solo career (though he continued playing on Waters' sessions per the Chess brothers' wishes).

A two-sided hit came next: "Sad Hours," an easy-rolling, dark-streets instrumental with an added reverb kick, backed with a slow, mournful vocal effort, "Mean Old World." Guitarist Louis Myers (with whom Walter had frequently toured) led a first-rate session group with members of his previous band The Aces: brother David Myers on guitar and drummer Fred Below. Credited on the label as The Night Caps (a typo?), both sides of the single were top ten R&B hits. Walter used this band, henceforth billed as The Jukes, on most of his recordings the next few years, a string of hits (most of them written by Little Walter under his partial birth name, Walter Jacobs) that includes "Tell Me Mama," "Off the Wall" (instro euphoria) and "Blues With a Feeling" in '53 and, in '54, "Oh Baby," "You'd Better Watch Yourself," "Last Night" and one of his best-selling and most recognizable hits, "You're So Fine."

The "big one" came out of a studio gathering in January 1955. "My Babe" was adapted by Willie Dixon from a 1920s gospel song, "This Train," recorded by many, perhaps most famously by Sister Rosetta Tharpe in 1939. The lyrics 'This train is bound for glory, this train..." became 'My babe don't stand no cheatin', my babe.' With Dixon on bass and guitarists Robert Lockwood Jr. (a regular sideman for Sonny Boy Williamson II, not to be confused with the first Sonny Boy) and Leonard Caston (formerly with Dixon's group The Big Three Trio) complementing Walter's signature harp work, it became his biggest hit at number one R&B in April and May 1955. With the rise of rock and roll, energized by Bill Haley and his Comets' chart-topping "Rock Around the Clock," certain black hitmakers of '55 became more than just R&B acts. Suddenly counted among rock's elite, Ray Charles, Fats Domino, Etta James, Smiley Lewis, Chess artists The Moonglows and Chuck Berry and Checker labelmates Bo Diddley and Little Walter (bluesman, rocker or both?) found themselves among the unexpected recipients of this increased attention.

Little Walter's contributions loomed large on the Muddy Waters recordings of this period including benchmark singles "I'm Your Hoochie Cooche Man," "Just Make Love to Me" ('I just wanna make love to you!'), "I'm Ready," "Manish Boy," "Trouble No More" and "Forty Days and Forty Nights." Walter's harp playing, besides on his own recordings, was essentially limited to Muddy's sessions. Other Chess-Checker acts could choose from a top-notch lineup of harmonica specialists (Howlin' Wolf's band featured teenage harpist James Cotton, a prolific player whose career thrived for more than six decades; Bo Diddley sometimes called upon Lester Davenport and Billy Boy Arnold, while Junior Wells remained on standby for whoever needed him). Walter's role in the majority of Muddy's recordings might make them sound, to the ears of certain listeners, like Little Walter songs with a different lead singer, though the singularity of Muddy's voice certainly overrides such a notion.

The hits kept coming: Walter linked up with Bo for the next one, "Roller Coaster," penned by Diddley and featuring his guitar backing. Bernard Roth, a butcher who lived just outside the Chicago metro in Gary, Indiana, moonlighted as a songwriter and scored a few times (with The Spaniels of the Vee-Jay label and Chess's own Muddy Waters). Bernie's contribution to Little Walter's repertoire was "Who" ('tole you...that I was foolin' around?') in early '56. The next two years brought a drought hit-wise, though you can't blame Dixon's top-notch production or the quality material: "One More Chance With You," instrumental scorcher "Flying Saucer" and perennial favorite "Boom, Boom Out Goes the Lights" (penned by Stan Lewis, responsible for several classics including Checker rocker Dale Hawkins' "Susie-Q"). Bluesy number "Key to the Highway" boasted a strong lineup including Otis Spann on piano, Waters on guitar, Dixon on bass and three other crack musicians, aiding Walter in his fall 1958 return to the top ten. He made the best seller lists again a year later with "Everything Gonna Be Alright."

The blues became a harder sell in the early '60s as its stepchildren rock and roll and rhythm and blues surpassed it in popularity. Some artists adapted to the changes while others held down the fort (and were ultimately rewarded for their perseverance). Of at least ten singles over the next seven years, only one by Little Walter came close to the national charts, a cringe-worthy reissue of "My Babe" with a chorus of pop singers dubbed in, not even worthy of one listen except out of curiosity. Yet a few stations played it and a small number of people bought it. One bright spot: The Rolling Stones made public their unabashed admiration for Walter and his extensive output. "Confessin' the Blues," one of his singles from 1958, was covered on their 1964 EP Five by Five in the U.K. and album 12 x 5 in the U.S. This validation, followed by a tour of the U.K. later that year, certainly gained him a new, slightly younger legion of fans. In 1967, he toured Europe as part of the American Folk Blues Festival.

When it came to his private life, Walter Jacobs was a loose cannon. A heavy drinker, he seldom backed down from a confrontation at a bar or on the street, a behavior flaw that got him into numerous scrapes and ultimately brought about his end. Exact details are a mystery, but this much is certain: in February 1968 he got into a fight with someone and was dead by the following morning. 37 years and several months, boom boom...you know the rest. The legend endures; Little Walter's amplified harmonica technique has influenced countless musicians and remains a preference for discerning modern-day players.

NOTABLE SINGLES:

- Ora-Nelle Blues - 1947

as Little Walter J. - Muskadine Blues - 1950

by Little Walter Trio - Just Keep Lovin' Her - 1950

by Little Walter Trio - Juke - 1952

by Little Walter and his Night Cats / - Can't Hold on Much Longer - 1952

by Little Walter and his Night Cats - Mean Old World - 1953

by Little Walter and his Night Caps / - Sad Hours - 1953

by Little Walter and his Night Caps - Don't Have to Hunt No More - 1953

- Tell Me Mama - 1953

by Little Walter and his Jukes / - Off the Wall - 1953

by Little Walter and his Jukes - Blues With a Feeling - 1953

by Little Walter and his Jukes - You're So Fine - 1954

by Little Walter and his Jukes - Oh Baby - 1954

by Little Walter and his Jukes - You'd Better Watch Yourself - 1954

by Little Walter and his Jukes - Last Night - 1954

by Little Walter and his Jukes - My Babe - 1955

by Little Walter and his Jukes - Roller Coaster - 1955

by Little Walter and his Jukes - Too Late - 1955

by Little Walter and his Jukes - Who - 1956

by Little Walter and his Jukes - One More Chance With You - 1956

by Little Walter and his Jukes / - Flying Saucer - 1956

by Little Walter and his Jukes - Just a Feeling - 1956

- Boom, Boom Out Goes the Lights - 1957

- Confessin' the Blues - 1958

- Key to the Highway - 1958

by Little Walter and his Jukes - My Baby is Sweeter - 1959

- Everything Gonna be Alright - 1959

- Ah'w Baby - 1960

- My Babe - 1960

- Crazy For My Baby - 1961

- Just You Fool - 1962

- Up the Line - 1963

- I'm a Business Man - 1964

- Mean Ole Frisco - 1965