THE RIGHTEOUS BROTHERS

Before bringing out The Righteous Brothers on a 1965 installment of ABC-TV's Shindig, host Jimmy O'Neill said fans had been sending in questions about the act such as, "Are they really brothers?" and "Are they really righteous?" He didn't offer any answers, going straight to the duo instead and they were exciting, as usual. Bill Medley and Bobby Hatfield, in fact, were one of those fortunate pairings: deep soulful voice meets high wailing soul man. It had happened before with black R&B acts. But for a couple of white guys from Orange County, California to come together and fit so well was less likely.

Medley was born and raised in Santa Ana. Hatfield's family moved from Beaver Dam, Wisconsin to Anaheim when he was a small child. Later, Bobby was not so musically inclined as he was athletic and in the late 1950s the Los Angeles Dodgers showed an interest in him. When that didn't pan out he began singing with a local group called The Variations. At about the same time, Medley was making records with local band The Paramours, a four-man outfit with two 1961 singles on the Smash label. The following year, Medley and keyboard player Johnny Wimber of the Paramours got together with Hatfield and the reconfigured group had a single on Moonglow Records, "There She Goes (She's Walking Away)," written by Medley. None of these three Paramours releases had much impact beyond the immediate families of the group members.

R.J. Van Hoogten, the owner of Moonglow, was interested in recording Bill and Bobby as a duo. The Paramours had been performing around L.A. to favorable reaction, particularly at clubs in the black neighborhoods where they were referred to, in '60s slang, as a "righteous" act. When it came down to just the two, The Righteous Brothers were born. Their influences were rooted in the rhythm and blues each had grown up hearing on the radio, primarily Ray Charles and nearby Pasadena, California duo Don and Dewey, after whom they initially patterned their vocal approach and stage moves.

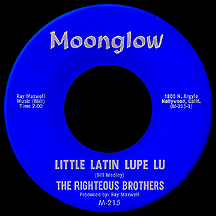

First up was a screamin' wonder of the world written by Bill, "Little Latin Lupe Lu." The song caught on quickly in Los Angeles, going top ten on the local top 40 stations in April 1963. Hitting the road to promote the single, they dropped in at many radio stations across the country, finding that quite a few R&B stations were playing the song. In some instances those same stations dropped the record from their playlists when they discovered the guys were white. Nationally the record didn't come near the success it enjoyed in L.A., peaking just below the top 40. A good start, though, no matter how you add it up. Follow-up "My Babe," a joint Bill and Bobby writing effort with more of a Ray Charles-style big band arrangement, nearly cracked the top ten locally in September but nationally went even lower than "Lupe." The live dates were still the duo's greatest strength, guaranteed to excite a crowd every time.

Medley was exerting more control in the studio as time went on, often working closely with producers Ray Maxwell, Jack Nitzsche and, later, Ahmet Ertegun (whose Atlantic label distributed the later Moonglow records), going so far as to completely dominate the producer's role whenever possible. Many of the Moonglow sessions were done in single takes with all the musicians playing at once. The Righteous Brothers liked the result that Bill called "leakage," with "drums going all around the room." Remaking Don and Dewey's jungle-themed "Koko Joe" from 1958, Bill and Bobby landed in L.A.'s top ten once again in early '64, yet the record went missing in action on the national charts. Okay, so they were big stars in and around their home turf of Southern California, but achieving anything approaching coast-to-coast coverage was proving difficult.

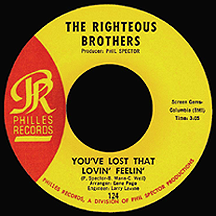

One city where they'd gotten a nice dose of airplay was San Francisco. During a show there at the Cow Palace later in the year, Phil Spector (who had a couple of his own Philles label acts on the bill) saw firsthand the excitement these so-called soul brothers incited and instantly wanted them to be part of his master plan to dominate the music industry. He approached Van Hoogten, dangled some cash, and cut a deal that gave him control of the Brothers and all record releases in the U.S., Canada and Britain for the next four years, while Moonglow retained rights to the act's recordings throughout the rest of the world. A song written by Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil (inadvertently sharing credit with Phil as cowriter after he made a minor change or two), "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" was envisioned as a Spectorized masterpiece of emotional excess, with all of the instruments swirling around the room in typical "Wall of Sound" fashion. And so with considerable effort it emerged as planned, arguably the apex of Spector's career and positively the defining moment for Bill and Bobby.

The elaborate production's final take ran about three minutes and 50 seconds. Nervous at the prospect of radio programmers rejecting the record (a bit long by mid-'60s hit standards) or worse yet editing it, effectively butchering this latest, greatest achievement and thereby compromising his artistic vision, Spector had the time printed on the label as 3:05, figuring no one would notice it actually ran longer. Most did eventually notice, but by that time it didn't matter; the December release was a smash, landing the duo at number one on the formerly daunting national chart in February 1965. In addition, the song was a top ten hit on the R&B charts, receiving heavy airplay on many of the stations that had resisted playing "Little Latin Lupe Lu" nearly two years earlier. At year's end in England, Cilla Black released a version of "You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'" that began climbing the charts, but Spector wasn't caught off-guard. He put a push on his record and it followed right behind Cilla's rendition. At the end of January, Black's single was at number two with the Righteous original right behind at number three; the following week (exactly as the song hit the top in America) the Righteous Brothers claimed their rightful place in the U.K.'s number one slot, as Cilla's not-quite-as-successful version began its descent.

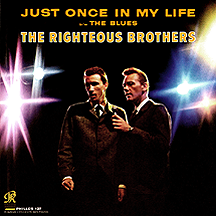

Philles Records engineer Larry Levine had to needle Spector somewhat to get him to agree that getting an album on the street quickly would capitalize on the smash hit, but Phil didn't want to be bothered with the production process on anything beyond the higher-profile singles. An album titled after the hit was released, with all other tracks on the set produced by Bill Medley. When follow-up Spector production "Just Once in My Life" (written by Phil, Gerry Goffin and Carole King) hit the top ten a few months later, another mostly Medley-helmed album was released. Both sold very well. Moonglow got some of the action too, putting out singles and albums of previous Righteous tracks (still owned by the label) and reaping reasonable returns. With Bill controlling most of the studio time, he let it be known he didn't really need Spector's input, which didn't set well with notorious control freak Phil. Van Hoogten had his own problems when Spector failed to deliver copies of some of the masters for Moonglow to distribute and promote overseas, so he filed a lawsuit. With so many overblown egos, sparks were bound to fly. The more low-key Bobby Hatfield had grievances too.

"Unchained Melody," which had been a hit for Les Baxter, Al Hibbler, Roy Hamilton and others in 1955, with many other notable versions in its ten years of existence including an uptempo 1962 doo wop interpretation by Vito and the Salutations, was given the Righteous treatment, but it wasn't intended to be a hit. "Hung on You" was the A side of the summer '65 single, but disc jockeys started flipping it over, showing preference for the "Unchained" flip, which featured only Hatfield's voice. In August it became the duo's third top ten hit of the year. Bobby, sandwiched between Spector's intimidating presence and Medley's increasing sense of self image, was feeling underappreciated. After the success of "Unchained Melody," with nary a peep from Medley on the track, he started considering a solo career as a possibility. Bottom line: each person involved had his own self-centered agenda. Everything was about to crumble. But not until after another major hit came out!

"Ebb Tide" was also a mid-'50s remake (most famously an instrumental hit for British bandleader Frank Chacksfield in 1953) and Spector's atmospheric production of the record gave the Righteous Brothers their fourth consecutive top ten in January 1966. While it was riding the charts, Medley and Hatfield (with Van Hoogten still attached) made a deal with MGM's Verve label after reaching an impasse at Philles Records. Phil Spector reportedly received a one million dollar buyout on their contract, and that was fine by him; he knew from experience with The Crystals, The Ronettes and other Philles artists that a year or so of big hits with one act was about all he could expect (not considering that if he handled his affairs differently, the success of those acts might not be quite so fleeting).

Mann and Weil supplied the first song for release on Verve, happy this time at not having to share writer credit with Spector, as they had begrudgingly done with "Lovin' Feelin'." "(You're My) Soul and Inspiration" was produced by Medley in an exact replication of Spector's trademark "Wall of Sound." Many were unaware at first of the move to Verve and when hearing it on the radio thought it was another Philles record (myself included). An instant smash, it became their second number one hit in April '66. Some involved received satisfaction from just the notion that they had trumped Spector, imagining his frustration at turning on a radio and hearing a hit Spectoresque record that he'd had nothing to do with (though Phil probably didn't care). Medley and Hatfield were certainly vindicated knowing that they could do it on their own, and Verve executives were satisfied they had made a solid investment. But was it all what it seemed to be? They got the answer to that unasked question sooner than anyone could have expected.

Reaching back to the '50s again, the next single was the inspirational "He" (a hit for Hibbler in 1955 as "Unchained Melody" had been). A top 20 hit, it fell below expectations, but that was a bar that would soon be set much, much lower. Each single seemed to regress when compared to the previous, from Medley's "Go Ahead and Cry" to Goffin and King's "On This Side of Goodbye" to the ones that followed as the Righteous sound became gradually dated and out of sync with the harder rocking and soulfully more progressive late '60s. Phil Spector had gotten the last laugh. The Righteous Brothers split up in 1968.

Hatfield recruited Jimmy Walker, former drummer for The Knickerbockers, to take Medley's place, but fans weren't fond of the switch and the adjusted act was short-lived. Medley had an encouraging solo run in 1968 with more Goffin-King and Mann-Weil material, placing three songs on the national charts, but none in the top 40. "Brown Eyed Woman" and the gospel-heavy "Peace Brother Peace" were, like the Moonglow singles a half-decade earlier, top ten hits in Los Angeles, but those were no guarantee of continued success. Bobby had a minor chart entry in 1969 with another mid-'50s remake, The Platters' classic "Only You (And You Alone)." For five years afterward, both singers seemingly disappeared from sight.

Bill and Bobby reunited in 1974, signed with Haven Records, and made a grand return to the top ten with the Alan O'Day-Johnny Stevenson-penned "Rock and Roll Heaven," cheesily paying tribute to Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Otis Redding, Jim Morrison, Jim Croce and Bobby Darin, artists who had died between 1967 and 1973. Two more hits in '74, "Give it to the People" and "Dream On," rounded out a solid year for the duo. After that the two toured for many years. Medley recorded a duet with Jennifer Warnes, "(I've Had) The Time of My Life," a number one hit in 1987 through its exposure in the blockbuster movie Dirty Dancing starring Patrick Swayze. In 1990, another hit Swayze film, Ghost, featured the duo's "Unchained Melody," a smash all over again for a new generation. The Righteous Spector classic hit the charts, as did a newly-recorded version on the Curb label.

Through all the ins and outs and ego bursts, The Righteous Brothers stayed in the public eye, off and on, from the 1960s through the 1990s. Now it's time for the answers you already know to Jimmy O'Neill's questions: No, they weren't brothers. Yes, they were righteous, happening, groovy, boss, out of sight, and any other grandiose adjectives you care to attach to them.

NOTABLE SINGLES:

- There She Goes (She's Walking Away) - 1962

by the Paramours - Little Latin Lupe Lu - 1963

- My Babe - 1963

- Koko Joe - 1964

- Try to Find Another Man - 1964

- This Little Girl of Mine - 1964

- You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin' - 1965

- Bring Your Love to Me /

Fannie Mae - 1965 - Just Once in My Life - 1965

- You Can Have Her - 1965

- Justine - 1965

- Unchained Melody /

Hung on You - 1965 - For Your Love - 1965

- Ebb Tide - 1966

- Georgia on My MInd - 1966

- (You're My) Soul and Inspiration - 1966

- He /

He Will Break Your Heart - 1966 - Go Ahead and Cry - 1966

- The White Cliffs of Dover - 1966

- On This Side of Goodbye - 1966

- Along Came Jones - 1967

- Melancholy Music Man - 1967

- Stranded in the Middle of Noplace - 1967

- I Can't Make it Alone - 1968

by Bill Medley - Brown Eyed Woman - 1968

by Bill Medley - Peace Brother Peace - 1968

by Bill Medley - This is a Love Song - 1969

by Bill Medley - Only You (And You Alone) - 1969

by Bobby Hatfield - Rock and Roll Heaven - 1974

- Give it to the People - 1974

- Dream On - 1974