CONNIE FRANCIS

Versatility is what made Connie Francis the fabulous star she was in the '50s and '60s and, by all rights, should still be today. Recently I looked up the word "versatile" in Webster's Dictionary and it gave this definition: (vur'se-tel') adj. Capable of doing many things with superior expertise, mus. ex. Connie Francis. Okay, you know I'm lying about that last part. But it wouldn't be so far from the truth if the entry had actually said that. Connie is an all-around, multi-faceted singer. There aren't many who could carry a bag of tricks like hers and excel at everything in that bag; among singers, she's one of the few exceptions to the rule. So how did this little three-year-old accordion squeezer, who later considered chucking her diva dreams to work as a stenographer, develop into one who does it all? And how did she pull it off when most singers are best advised to stick with the one or two things they do best? I really don't have a clue how. Nevertheless, she did it, and an hour spent listening to a cross-section of her recordings covering pop, rock, jazz, blues, country, R&B, several genres of ethnic and foreign language songs, and even the occasional operatic passage, should convince anyone I speak the truth.

It all started with the accordion, that kinda-wind, kinda-string instrument that looks like a typewriter and a radiator rolled into one (that description taken from my own "Idiot's Guide to Musical Instruments"). George Franconero played one and it wasn't long until his daughter, Concetta Franconero, wanted to follow suit. When she was three years old, in 1942, the Newark, New Jersey girl was already quite familiar with this instrument not much smaller than she; at age four she played "O Sole Mio" in front of an audience and met with thunderous applause. From that moment on, a career in show business was her single-minded goal. Singing was a natural offshoot and before long she was memorizing every song she heard while dad schooled her in the finer points of accordion technique.

At the age of ten, in 1949, she performed on Marie Moser's Starlets, a Newark TV show, as a singing squeeze-boxer. She took the accordion with her to Ted Mack's Amateur Hour in 1950 and sang W.C. Handy's "St. Louis Blues." Some local New York-area television appearances followed, then the big one in December: Arthur Godfrey's Talent Scouts on CBS, where she used the name Connie Franconero for the last time. Godfrey suggested Francis would be easier to pronounce; she went along with the idea and grew to like it. In 1951 she joined the cast of NBC-TV's The Star Time Kids, a children's series that originated in New York City (future movie star Joe Pesci, also from Newark, joined the ensemble cast a couple of years later when he was ten). For four years she sang and performed skits on the series while continuing to sharpen her skills, on and off camera; in 1953 she competed in a championship typing competition...and won!

By the time she was 16, Connie had a nice sideline job recording demonstration discs for New York music publishers. Her ability to mimic popular singers along the lines of Rosemary Clooney and Joni James made her attractive to songwriters hoping to score hits with those singers, but after awhile Connie, anxious to develop her own sound, grew tired of the routine. Star Time Kids producer George Scheck became her manager and, after several major record labels turned her down, he negotiated a deal with MGM. Though not yet a high school graduate, she found herself alternating between nightclub appearances (with her parents' permission as required by law for underage performers) and studio recording. Her first session in the spring of 1955 resulted in a bouncy tune called "Freddy," resembling something perhaps more suited to the vocal styles of Teresa Brewer or Jill Corey; Connie hit a couple of off-key notes and her performance revealed a bit of nervousness, which you won't find on any other finished take. The song was released as her first single, likely because one of the MGM executives had a nephew named Freddy and the song was part of the reason she was signed to MGM in the first place. It was her first failure, but the situation worsened with each successive release.

Finding her comfort zone while trying to fit in somewhere amongst the female stars of the mid-'50s was difficult indeed. Several months after those first MGM sessions she met Bobby Darin, a Brill Building staff writer at the time. "My First Real Love," written by Darin with George Scheck and Don Kirshner, was her fourth single release (with backing vocals by The Jaybirds, a nom de plume for a multitracked Bobby D.) and fell into the same abyss as the first three. Undaunted, Darin possessed a positive outlook and confidence in his own abilities that proved irresistible to Connie. Romance blossomed. The two at one point planned to elope (Connie has said it was more his idea than hers...she was just 17!), but her father caught wind of it and threatened Bobby with a gun, which decidedly ended the relationship.

Connie and her main producer, Harry Meyerson, tried different approaches in those first two years, mostly staying with pop productions while experimenting with country and R&B arrangements. Nothing worked. She auditioned for a role in Rock, Rock, Rock!, but ended up dubbing the singing voice for Tuesday Weld, who won the lead role in the film, released in December 1956. Doubt had been cast on MGM's commitment to promoting her image, a realization that came as a crushing blow. Singles kept coming out; two years and nine stiffs in a row. The label's honchos were growing restless. Her days were numbered. MGM came close to cutting her loose towards the end of 1957.

A temporary reprieve came in near-hit form when the label paired her with Marvin Rainwater for her tenth single release. A country singer of part-Cherokee Indian ancestry, Rainwater had achieved huge success with "Gonna Find Me a Bluebird" in the spring of '57 but was having trouble following the hit. MGM booked a session for the two; "The Majesty of Love" was released with Connie receiving second billing (a logical decision) and the record began picking up airplay. In December it spent one week on the low end of the national chart, a failure by normal standards but an encouraging sign for Connie. MGM decided to take one more shot before giving her the boot, but she was already a step ahead of them. Despondent over a frustrating three years, filled with doubts over her place (or lack thereof) in the music business, she decided to leave it all behind, reasoning she could make a better living if she studied in the medical field or perhaps made use of her typing skills by taking a stenographer's job that had been offered her. She entered her final recording session with a "Who cares anymore?" attitude.

Her father asked her to record one of his all-time favorite songs, "Who's Sorry Now?," a revenge ballad of sorts ('...You had your way, now you must pay...I'm glad that you're sorry now"). Written by Ted Snyder, Bert Kalmar and Harry Ruby in 1923, it was most popularly recorded as an instrumental that year by bandleader Isham Jones and was also a vocal hit for Marion Harris. One last chance at recording a potential hit and he wanted her to squander it on a stodgy old ballad! Connie refused at first, the senior Franconero insisted, an argument ensued and she gave in. 19 years old and soon to be a has-been, disappointed over the depths her once-promising profession had fallen to, she sleepwalked through the song in two takes at the end of her final scheduled session in October 1957. Then she left the studio feeling stronger than ever that her longed-for career in music had just ended.

MGM released it as her eleventh single. Dick Clark received a promotional copy and liked the big band-meets-teen-ballad approach; once he played it on American Bandstand in January 1958, "Who's Sorry Now" (minus the question mark in the title) quickly developed a following. By March, it was a top ten hit. Connie's career had been saved in the last possible ten minutes of studio time. MGM renewed her contract while she consulted her dad on which old song she should revive from the dead for her next hit. "I'm Sorry I Made You Cry" got the nod, an even older tune that had topped the charts for early 20th century superstar Henry Burr in 1918. Her remake barely made the top 40, a disappointing attempt at a second major hit.

"Heartaches," a slightly more "contemporary" song (from the 1930s) was completely ignored. George Franconero's taste in music had resulted in what Connie once called "One and a half hits." It was time to switch gears. Up-and-coming songwriters Neil Sedaka and Howard Greenfield pitched a number of old-timey-type ballads they had written to the still-teenaged Francis but she was unimpressed; then Neil played the silly-but-catchy "Stupid Cupid" and she was hooked! This song would drive her old man off the deep end, but it had hit written all over it! In the studio she launched into an over-the-top lyrical parody of juvenile romance: '...Since I kissed his lovin' lips of wine...the thing that bothers me is that I like it fine!' Critics who'd bristled at "Who's Sorry Now" rolled their eyes and shook their heads. The public rushed to buy it. "Stupid Cupid" was a smash and, in the process, Connie Francis hit on a formula: mix things up, keep 'em guessing.

She was gradually working her charms on the rest of the world and would later go after an international audience with full-on intent. British fans were slower to accept her as a rock-and-roller; "Who's Sorry Now" had already hit number one in the U.K., and it was the flip side of "Stupid Cupid," "Carolina Moon" (a 30-year-old chestnut) that repeated the feat in the fall of '58. Back home she followed with another Sedaka-Greenfield creation, "Fallin'," a wickedly confident rock song with clever Biblical references, then reversed herself again with "My Happiness" (another '30s tune), a number two hit in early '59, her biggest yet, followed by an off-kilter remake of The Ink Spots' signature tune from 1939, "If I Didn't Care."

For six months from March through September '59 she was a regular performer on the NBC variety series The Jimmie Rodgers Show, the weekly exposure to television viewers helping accelerate the speed at which her star was rising. The next hit, "Lipstick on Your Collar," written by Edna Lewis and George Goehring, found Connie reading the riot act to some unidentified loverboy; the single's B side, "Frankie," permanently archived her admitted crush on teen star Frankie Avalon through the music and lyrics of Sedaka and Greenfield. Each side was a top ten hit in the summer of '59. Connie indulged in some songwriting of her own and hit the charts in the fall with "Plenty Good Lovin'," then took another unforeseen turn with "God Bless America" (the Irvin Berlin classic made famous in the late '30s by Kate Smith), her attempt to give teenage fans their own version of the patriotic classic. That record's B side, "Among My Souvenirs" (a previous number one for the Paul Whiteman orchestra in 1928), became her fifth top ten hit in less than two years.

Reviving her father's favorite songs from the '20s and '30s had worked so far, but how long could she stay relevant alternating current teen tunes with the hits of a generation passed? The next single signified a new direction, one she had been considering for some time: recording in her family's native tongue. Turns out the idea and its execution rapidly gained approval with Italian immigrants, a large segment of the U.S. population. As well as their relatives back home. In addition to anyone who had a soft spot for mom, which is just about everyone. For several months she had been performing "Mama" at live shows; first written in 1941, the Italian song with added English lyrics hadn't been considered for single release for several reasons including its nearly four minute length. When it was released in early 1960 as a single from the album Connie Francis Sings Italian Favorites, the song went top ten while winning over many remaining skeptics as to her vocal range and depth of song selection. It also gave her career a new lease on life...not that she needed one at the time. The LP became the biggest selling of her entire career and laid the basis for a long series of internationally-oriented albums including Spanish and Latin American Favorites, Jewish Favorites and other collections of Irish, German, Hawaiian, several more Italian offerings, and even an album of foreign language standards from a variety of sources.

MGM Records had given Connie carte blanche when it came to musical selections and she explored every possibility, coming up a winner every time. "Everybody's Somebody's Fool," written by Howard Greenfield and Jack Keller, leaned in a country direction but connected across the board, becoming her first number one hit in July 1960 (and a top 30 country hit). A German version, "Die Liebe ist ein Seltsames Spiel" (which translates as "Love is a Strange Game"), was a number one Deutschland smash in October; after this she recorded each new single in several different languages. The U.S. B side, "Jealous of You (Tango Della Gelosia)," went top 20 and was her first American hit with all-Italian lyrics, a rare occurrence for an American artist.

Connie's newfound legitimacy among critics and extended reach among listeners didn't cause her to abandon the all-important teen market (in the U.K., far-fetched oddity "Robot Man" was the hit B side to "Mama"), but she took a noticeably more mature approach with successive releases. Another Greenfield-Keller song, "My Heart Has a Mind of Its Own," returned her to number one in September; its flip side, the classic "Malagueña" from Ernesto Lecuona's late-'20s "Suite Andalucia," won favor with Latin music fans in much the same way Italians had embraced her earlier in the year. She adapted "Many Tears Ago," a rhythm and blues song by Winfield Scott of The Cues, into a no-nonsense pop song and another top ten hit. Then came the inevitable career move many have taken yet few have mastered: Hollywood beckoned, movie stardom awaited.

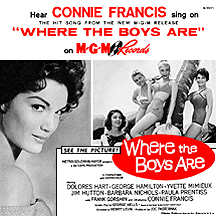

A small part in a December 1959 episode of United States Steel Hour had paved the way for another minor role in a major studio film, Where the Boys Are (Dolores Hart, George Hamilton and Yvette Mimieux headlined the fun-in-Fort Lauderdale feature), but it was perceived as a Connie Francis star vehicle due largely to its spectacularly-produced Sedaka-Greenfield theme song, a major hit in early 1961, shortly after the film's release. Flip side "No One," written specifically for her by Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman, made its mark as well with many interpretations over the years by singers including Ray Charles and Brenda Lee. Meanwhile, Connie focused much of her time studying the musical styles of many countries from around the globe; her heart was in Italy, of course, and in the spring, "Jealous of You" became her first number one hit there ("Where the Boys Are" also topped the Italian charts that year).

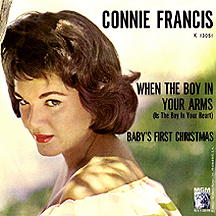

Her eleventh American top ten, "Breakin' in a Brand New Broken Heart," was yet another Greenfield-Keller tune and brought her to closer than ever to a C&W sound, though it didn't hit the country charts. For her 12th top ten hit she dipped back into Paul Whiteman's 1928 hit list with "Together," adding a romantic spoken passage, a new trick she revisited from time to time. John D. Loudermilk contributed a pair of songs for the next single: "Hollywood" (not about the California town but a guy she admired) was the intended hit side, but "He's My Dreamboat" (containing a similar object of desire) went higher on the charts. Cliff Richard's Brit hit "When the Girl in Your Arms" supplied the inspiration for her next single, the gender-adjusted "When the Boy in Your Arms (Is the Boy in Your Heart)." Its flip side was her best shot at seasonal longevity; she targeted young married couples with the Benny Davis-Ted Murry song "Baby's First Christmas," performing it from atop a float during Macy's 1961 Thanksgiving Day Parade.

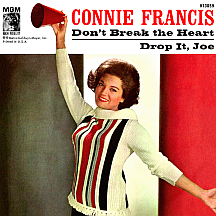

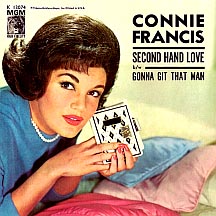

"Don't Break the Heart That Loves You," also written by Davis and Murry, became Connie's third number one hit in March 1962. Phil Spector got involved with her next top ten hit, "Second Hand Love," supplying the melody for Hank Hunter's lyrics. Hunter and Gary Weston came up with "Vacation," with added lyrics by Francis; during the summer of '62 it became her 16th top ten pop hit, a level achieved by no other solo female artist during the 1950s and '60s. In the fall she tackled a couple of country ballads, "I Was Such a Fool (To Fall in Love With You)" and the Dickey Lee-Steve Duffy song "He Thinks I Still Care," a number one country smash earlier in the year for George Jones as "She Thinks I Still Care." For the 1962 holiday season she bypassed a Christmas song in favor of "I'm Gonna Be Warm This Winter," depicting an idealized image of romance at a ski lodge, backed by her well-received rendition of Italian idol Emilio Pericoli's recently-realized hit, "Al Di La.".

After the experience of making her first film, Connie had no further interest in pursuing a movie career, but her manager and the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer film studio felt differently. She was cajoled into signing a three-picture deal; the first of these appeared more than two years after Where the Boys Are with a suspiciously similar title. She had the lead role this time in Follow the Boys, observing from a not-so-safe distance the exploits of four women who did just what the title implied. Despite tepid reviews, the film was a success and its theme song by Davis and Murry was a hit. She starred in two more productions, 1964's Looking For Love and 1965's When the Boys Meet the Girls (the latter made more lively with performances by Sam the Sham and the Pharaohs, Herman's Hermits and Liberace). One final role as a nun in a 1966 episode of Bob Hope Presents the Chrysler Theatre and she gave up acting for good.

From 1963 through the end of the decade, her record sales gradually declined. Some of the better songs from this later period include "Your Other Love," a Claus Ogerman production done girl group style, and "In the Summer of His Years," a tribute to John Fitzgerald Kennedy first performed by Millicent Martin on a special episode of the BBC television series That Was the Week That Was following his assassination in November 1963; Connie recorded her hit version shortly afterward. "Blue Winter" seemed an appropriate choice for what had become a gloomier-than-usual holiday season and was the next release. "Bossa Nova Hand Dance" with its 'kookie rhythm' and "Love is Me, Love is You" (written and produced by Tony Hatch, taking a little time away from his ongoing projects with Petula Clark) were uptempo pleasures that deserved wider exposure.

With the dissipation of record sales in the late 1960s, Connie focused most of her energy on live performances, particularly in overseas venues where demand for her, in some cases, was as strong as it had been years earlier. By the 1970s the American public was focusing more on her personal difficulties than her music; marital problems, illnesses and two miscarriages kept her on the front pages of tabloids, providing the catalyst for Connie's many bouts with depression. She continued recording and had one minor chart single in 1973, "Should I Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree?," an answer to Tony Orlando and Dawn's massively popular "Tie a Yellow Ribbon..." that served as a reminder her peak years were far behind her. Then something happened the following year that nearly destroyed her life.

In November 1974, she was appearing at the Westbury Music Fair in Long Island, New York, at the beginning of a scheduled tour that would take her across the country. During the early morning hours of November 8, an intruder broke into her hotel room, molested her and departed with some of her valuables; he was never apprehended. The mind-numbing experience affected her deeply for several years afterward. Attempts at resuming her career fell flat as severe depression took hold for the rest of the decade and well into the 1980s. Then Connie's brother was killed in 1981 under mysterious circumstances that were likely mob-related. Numerous hospital stays contributed to thoughts of suicide, but thankfully that did not become a major issue.

She did manage to get a few records released and one of these, "There's Still a Few Good Love Songs Left in Me," spent a few weeks on the country charts in 1983. Her best-selling biography, Who's Sorry Now?, was published in 1984 and she gradually resumed her performing career while becoming actively involved in the rights of rape victims, advocating and lobbying for policy changes on violent crime through a task force granted her under the administration of President Ronald Reagan. She was involved in other human rights issues though the years and continued performing on a regular basis. Connie Francis survived extreme highs and lows with her spirit intact. She's one of the all-time greats in more ways than one.

NOTABLE SINGLES:

- Freddy - 1955

- My First Real Love - 1956

with the Jaybirds - The Majesty of Love - 1957

with Marvin Rainwater - Who's Sorry Now - 1958

- I'm Sorry I Made You Cry - 1958

- Stupid Cupid /

Carolina Moon - 1958 - Fallin' /

Happy Days and Lonely Nights - 1958 - My Happiness - 1959

- If I Didn't Care - 1959

- Lipstick on Your Collar /

Frankie - 1959 - You're Gonna Miss Me /

Plenty Good Lovin' - 1959 - God Bless America /

Among My Souvenirs - 1959 - Mama /

Teddy - 1960 - Robot Man - 1960

- Everybody's Somebody's Fool /

Jealous of You (Tango Della Gelosia) - 1960 - My Heart Has a Mind of Its Own /

Malagueña - 1960 - Many Tears Ago - 1960

- Where the Boys Are /

No One - 1961 - Breakin' in a Brand New Broken Heart - 1961

- Together /

Too Many Rules - 1961 - (He's My) Dreamboat /

Hollywood - 1961 - When the Boy in Your Arms (Is the Boy in Your Heart) /

Baby's First Christmas - 1961 - Don't Break the Heart That Loves You - 1962

- Second Hand Love - 1962

- Vacation - 1962

- I Was Such a Fool (To Fall in Love With You) /

He Thinks I Still Care - 1962 - I'm Gonna Be Warm This Winter /

Al Di La - 1963 - Follow the Boys - 1963

- If My Pillow Could Talk - 1963

- Drownin' My Sorrows - 1963

- Your Other Love - 1963

- In the Summer of His Years - 1964

- Blue Winter - 1964

- Be Anything (But Be Mine) - 1964

- Looking For Love - 1964

- Don't Ever Leave Me - 1964

- Whose Heart Are You Breaking Tonight - 1965

- For Mama - 1965

- Wishing it Was You - 1965

- Forget Domani - 1965

- Roundabout /

Bossa Nova Hand Dance - 1965 - Jealous Heart - 1965

- Love is Me, Love is You - 1966

- A Letter From a Soldier (Dear Mama) - 1966

- Spanish Nights and You - 1966

- Another Page - 1967

- Time Alone Will Tell - 1967

- The Wedding Cake - 1969

- Should I Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree? - 1973

- There's Still a Few Good Love Songs Left in Me - 1983