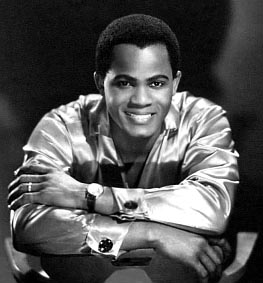

JOE TEX

In 1965, Joseph Arrington, Jr. had his first big hit, "Hold What You've Got." Perseverance got him to that point as he'd been making records for almost ten years. Nicknamed Joe Tex from the start, this native of Rogers, Texas was a cool guy. He had advice for everyone, especially when it came to romance and moral behavior. The long road to stardom got under way in 1955 when he made the journey from the Lone Star State to New York City's Apollo Theater, taking control of the crowds and coming in first place on more than one "Amateur Night." Syd Nathan, owner of King records, offered him a chance to record, and his debut, the self-penned "Come in This House," came out in early 1956. After several releases but no breakthrough hit, King cut him loose and he headed back to Texas, where he served as a minister in Baytown, located just west of Houston on Galveston Bay, around 1957 and '58.

Going to Jackson, Mississippi would hardly seem a logical next step, but Johnny Vincent had a good thing going there with his Ace record label, headquartered just a couple hundred miles north of New Orleans. Many of the Ace acts recorded in the Crescent City at Cosimo Matassa's studio, resulting in purely magical tracks like "Don't You Just Know It" by Huey (Piano) Smith and the Clowns and "Sea Cruise" by Frankie Ford. Tex joined the Ace roster in 1958 and waxed several singles at Cosimo's but, as had happened with King Records, none were hits. Where his efforts for King had been more standard R&B, he mixed things up at Ace, trying novelty tracks ("Charlie Brown Got Expelled," a too-close-for-comfort variation on The Coasters' "Charlie Brown" and "Grannie Stole the Show" about a hotsteppin' octogenarian) and relationship message songs like "Mother's Advice," along with some New Orleans-style numbers closer to the Ace standard. None of it worked, though a series of Dear Abby-style advice tracks would eventually become something of a trademark for Joe. He also perfected some mean dance moves, including an impressive microphone stand gimmick by letting the stand fall to the floor as he grabs it with his foot just in time, proceeding to kick it around while dancing and singing, never missing a beat of the song. Those kinds of stage moves became another Joe Tex trademark but would later get him into a skirmish with a certain "Mr. Dynamite."

Joe had a Motown connection in 1960 with a few singles for the Anna label, owned by Berry Gordy's sister Anna Gordy. The first was a Gwen Gordy-Billy Davis-Berry Gordy ballad, "All I Could Do Was Cry," which became a top 40 hit for Etta James in June. Joe's take on the song had two parts, the flip side a spoken discourse lamenting love lost, and it showed up on Billboard's "Bubbling Under" chart in August, his first single to garner any national exposure. Another Anna single later reissued by Ace, "Baby You're Right," was interpreted with minor changes by James Brown (who added his name alongside Tex on his 45's songwriter credit) and hit the pop charts, and R&B top ten, exactly one year later, the first major hit with Joe's name attached. Any good feelings Joe had towards James was short-lived, though, when the latter made claims that the former had copied his moves onstage. Joe's reply was to make fun of JB's cape-wearing "Please, Please, Please" routine at a concert, and when James began dating Joe's ex-wife, Bea Ford (with whom he'd duetted on "You've Got the Power"), the two cut ties permanently.

The break of a lifetime came when Joe met William "Buddy" Killen. Feeling frustrated after several years without making much progress in the business, he auditioned for Killen in 1961. Buddy worked for Big Tree Publishing in Nashville and had written one of the great melodies of the 1960s, "Forever," a hit for The Little Dippers in 1960, and shortly afterwards he worked with a teenage Dolly Parton, then a Mercury artist, on some of her early efforts (many more country music projects followed through the years). Tex and Killen clicked when they first met and a deal was struck wherein Killen created a record label, Dial, specifically for the purpose of releasing and promoting Joe Tex records. Ten singles came out on Dial between 1961 and 1964, repeating what had happened at King and Ace to excess. The songs, all written by Joe, included more of his ballads with spoken advice passages, novelty tunes and a few outright solid soul shouts; basically the same formula he'd used at Ace, with the same frustrating results. Joe was ready to call it quits and move on well before the tenth record (and, in fact, had done some moonlighting with releases on Chicago's Chess Records and the Michelle label out of Baton Rouge, Louisiana). Killen convinced him to hang in there a little longer.

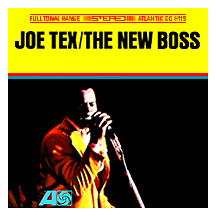

"Hold What You've Got," from a session at the FAME studios in R&B epicenter Muscle Shoals, Alabama, had a gospel vibe and a bit of a country lean, ingredients Tex had tried before. The song's spoken reprimand ('If you think no other man wants her, just throw her away and you will see...some man will have her before you can count...one-two-three') was in line with earlier Tex tracks too. But this time people sat up and paid attention. The late '64 release went top ten on the pop charts and number one R&B in January 1965. The National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences didn't waste any time jumping on Joe's now-rolling bandwagon. The song received a Grammy nomination for Best Rhythm and Blues Recording before it had even fallen off the charts. He'd become an "oversnight sensation" at the start of his second decade as a recording act.

The next 45, "You Better Get It," followed the preachy pattern of the previous record, but he loosened up on the flip, "You Got What it Takes," a smooth and soulful midtempo groove. Succeeding singles alternated between Joe's relationship observations (often containing an inspirational moral rooted in his deep-seated religious beliefs) and genuinely funkier R&B more in line with what the artists of Dial's distributing label, Atlantic Records, were doing. Tex gushed with playful romantic emotions on "I Want To (Do Everything For You)" and "A Sweet Woman Like You." Those back-to-back 1965 releases returned him to the top 40 and became his second and third number one R&B hits. He dug a little deeper in 1966 with "The Love You Save" and breached the political landscape with "I Believe I'm Gonna Make It," describing a Viet Nam soldier writing a letter home, one of the earliest songs to acknowledge that ever-increasing far east conflict. "S.Y.S.L.J.F.M. (The Letter Song)" lightened things considerably with whimsical, if somewhat silly, wordplay (the letters standing for 'save your sweet love just for me'). Joe closed out the year defending his country loverboy ways on "Papa Was Too," a variation on Lowell Fulsom's hit "Tramp," riding the charts at the same time.

The Tex-Killen team was a well-oiled machine in those hitmaking years of the mid-to-late 1960s and the two became very close friends. Buddy produced and Joe continued doing all the songwriting himself, as if writing a large-scale book containing fiction and nonfiction chapters. Originality suffered at times, perhaps due to the sheer volume of output, as Joe adhered to the same general formula he'd been comfortable with since the late '50s. From time to time the stars aligned, though, like when he caught a hot groove in 1967 with "Show Me," one of the highlights of his career. Sure, it had repetitious lyrics ('Show me a man that's got a good woman'...'show me a woman that's got a good man!'), but it was one of the year's best. I challenge you to stay in your seat while it plays. At year's end he offered the craziest mess to date, "Skinny Legs and All," a potentially offensive novelty hit depicting Joe and his buddies passing around an unwanted woman (not unlike an auction: 'Who'll take the woman with the skinny legs?') until one of the guys, Leroy, has her forced upon him. The record was produced in the studio with a small crowd (mostly Joe's "friends" cutting up), then later played for a larger audience dubbed in to give it a "live" feel. It was a smash hit beyond all expectations; top ten, a million seller and Grammy nominee to boot. A similar pseudo-live novelty from the same session, "Men Are Gettin' Scarce," hit the airwaves in early 1968.

Tex then took part in a one-off Atlantic Records "soul supergroup" session, joining with Solomon Burke, Arthur Conley, Don Covay and Ben E. King in 1968 as The Soul Clan. "Soul Meeting" was no more than just good fun, a chance for the five established stars to take turns on each verse and shout out...well, to themselves. As the decade wound down, Joe's career slowed down. By the early 1970s he had converted to the Muslim faith, changing his name to Yusuf Hazziez while continuing to make records under his famous stage name. The biggest hit of his career was still on the horizon. "I Gotcha" upped the percentage of screaming, sexual demanding ('Now give it here...don't hold back, now give it here!'), taking him to number two in the spring of 1972, to number one for the fourth time on the R&B (renamed Soul) charts and into Grammy contention, a regular fixture now in the category of Best R&B Vocal Performance, Male. Clearly he was leading two lives; religious motivational speaker by day...wild-eyed, rubber-legged, fun-loving singer by night.

By now you might be wondering if he ever won the Grammy Award. Or if, perhaps, he decided to completely devote himself to his faith. Unfortunately the answer is no on both counts. With disco music dominating in 1977, Tex, still cozy with Buddy Killen, took his music to a new low with "Ain't Gonna Bump No More (With No Big Fat Woman)," released on Epic Records (written by Killen and Bennie Lee McGinty, it was the only hit song not written by Tex and the first in a very long time on a label other than Dial, though he would later resume with that label). The earlier pattern repeated itself with somewhat distressing excess: big hit, million seller, Grammy nomination (his fourth and second loss to Lou Rawls). Joe/Hazziez had stepped beyond the lines of taste and/or common sense, yet received positive notice for musical excellence (it was the ever-inconsistent Grammys, whatcha gonna do?)

His talent and energy was obvious, but I don't think Joe ever quite set his priorities straight. Leaving the business, likely with the intention of returning yet again, he mostly kept to himself at home in Texas in the early 1980s until his death of a heart attack at age 49 in August 1982. It's been suggested by Killen and others that he may have been consumed by the bottle and other substances during that time, in stark contrast to a previously insistent teetotaling attitude. All said and done, Joe Tex was a phenomenal performer and prolific songwriter possessing a wide range of talent running the gamut from the motivational and spiritual to the occasionally ridiculous, covering all the emotions in between with sincerity and style.

NOTABLE SINGLES:

- Come in This House - 1955

- My Biggest Mistake - 1956

- You Little Baby Face Thing - 1958

- Charlie Brown Got Expelled - 1959

- Grannie Stole the Show - 1960

- All I Could Do Was Cry - Part 2 - 1961

- Baby You're Right (I'm Gonna Hold What I Got) - 1961

- The Next Time She's Mine - 1964

- Hold What You've Got - 1965

- You Better Get It /

You Got What it Takes - 1965 - A Woman Can Change a Man /

Don't Let Your Left Hand Know - 1965 - One Monkey Don't Stop No Show - 1965

- I Want To (Do Everything For You) - 1965

- A Sweet Woman Like You - 1965

- The Love You Save (May Be Your Own) - 1966

- S.Y.S.L.J.F.M. (The Letter Song) - 1966

- I Believe I'm Gonna Make It - 1966

- I've Got to Do a Little Bit Better - 1966

- Papa Was Too - 1966

- Show Me - 1967

- Woman Like That, Yeah - 1967

- A Woman's Hands - 1967

- Skinny Legs and All - 1967

- Men Are Gettin' Scarce - 1968

- I'll Never Do You Wrong - 1968

- Soul Meeting - 1968

by the Soul Clan - Keep the One You Got - 1968

- You Need Me, Baby - 1968

- That's Your Baby - 1969

- Buying a Book - 1969

- That's the Way - 1969

- Give the Baby Anything the Baby Wants - 1971

- I Gotcha - 1972

- You Said a Bad Word - 1972

- Ain't Gonna Bump No More (With No Big Fat Woman) - 1977