MARY WELLS

One evening in 1960, Berry Gordy was at a Detroit nightclub where a couple of the acts on his recently-formed record label were performing. A 17-year-old girl boldly came up and told him she had written a song. He told her to sing it for him, and she did, quite well in fact, so he then told her to stop by his offices on West Grand Boulevard the next day. When she arrived with her mother at the house that had been converted into a recording studio and would later be christened "Hitsville U.S.A.," she explained that the song was written with singer Jackie Wilson in mind. Why Wilson? Well, she was certain that Gordy worked with the famous singer (but didn't realize their affiliation had ended more than a year earlier). No problem, though; Gordy had already decided the night before that the girl, whose name was Mary Wells, would be the one to record the song. He was looking for a young female singer to groom into star material (having already released a single by the older Mable John without much luck) and decided to take a chance on her. Mary's assertiveness and promising impromptu audition had impressed him.

Mary's life hadn't been easy up to that point. Growing up in a poor, single-parent home, she had suffered with childhood diseases and wanted desperately to make a better life for herself. Inspired by the music she heard on the radio, and aware that there were several Detroit-area record companies (prior to the appearance of Gordy's Tamla Records), she set a goal of becoming a songwriter, lacking the confidence or vision that she herself might someday actually be a singer as well. But her later glory began because she had the guts to approach Berry Gordy, and that audition song, "Bye Bye Baby," became her first release on the Motown label (which had been added as a Tamla subsidiary in late 1959) and first hit, making it to the top ten of the R&B charts and close to the pop top 40 in April 1961. She had a raw, raspy sound that, coupled with the song's lyrics ('...you took my love, threw it away...you're gonna want my love someday...well-a bye bye baby!'), made her seem like a "tough girl," but after the first few 45s she evolved into something altogether different with a soft, innocent-but-sexy style that would be the essential ingredient of several major hits.

Gordy produced the early Wells singles and wrote "I Don't Want to Take a Chance" with William Stevenson. That second release did even better than the first, but when Stevenson's "Strange Love" struggled out of the gate, Gordy put Mary's fate in the hands of Smokey Robinson, who thrived on challenging himself beyond the boundaries of his own hitmaking Miracles. Producing the record with backing vocals by Motown session singers The Love Tones, Smokey gave "The One Who Really Loves You" an unusual calypso-meets-Chinatown beat and the result was an across-the-board smash for Mary in June 1962, landing her in the pop top ten for the first time. The romantic leanings of this and Mary's subsequent releases proved irresistible to young female fans, and "You Beat Me to the Punch" (written by Smokey and Miracles partner Ronnie White) sent her back to the top ten in September and to number one on the R&B charts, another first. Come Grammy Awards time, she received a nomination for "You Beat Me," a first for any Motown act, under Best Rock and Roll Recording (losing to Bent Fabric's instrumental "Alley Cat," a bizarre category-bending development if there ever was one). She never had the chance to compete on a more logical level, as it was the only Grammy nod of her career.

"Two Lovers," another Robinson composition, gave Mary a chance to fool listeners into thinking she was playing the field until a shrewd split-personality twist revealed '...in reality, both of them are you...' The mini-soap opera had a maximum impact in early 1963, her third consecutive top ten hit and second R&B chart-topper. Mary's smooth, easygoing approach (which she'd developed since Smokey had begun working with her) perfectly augmented the seemingly scandalous lyrics. Though still in her teens, Mary married Herman Griffin (a Motown artist during the company's early stages) and settled into domestic life...or at least tried to. By this time she was neck-and-neck with the Miracles as the label's most popular act and headlined many of the talent-packed Motortown Revue concert tours, basking in all the attention from fans. Mary was quite the fashionista, keeping up with the latest styles and occasionally creating a look of her own, appearing in public wearing showy gowns while donning a variety of wigs, be they bouffants or longer styles in shades of brunette and blonde.

Next up was "Laughing Boy," a Smokey song, and "Your Old Stand By" by Smokey and "Money (That's What I Want)" cowriter Janie Bradford (who was living the songwriter's life Mary had originally imagined for herself). In the fall of '63, "You Lost the Sweetest Boy," written and produced by superstar team-in-the-making Eddie Holland, Lamont Dozier and Brian Holland, broke up the Smokey string, but Robinson rebounded by writing the biggest hit of Mary's career, "My Guy," a number one blockbuster in May 1964 (reaching the summit the same week as her 21st birthday), a hit so widespread that it became the number one R&B record of the entire year.

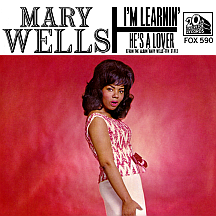

Suddenly, at a time when Wells should been visible everywhere, no one at Motown seemed to be able to get in touch with her. When Berry Gordy finally did come in contact, she had little to say except "I think you should talk to my lawyer." Unhappy with the deal she had made with the company at 17, and now of legal age, she sought to exercise her rights as she saw them. Despite there being three years left on her contract with Motown, she began accepting offers from other record companies. Gordy tried to convince her this was unheard of, but her belief was that she had been taken advantage of. 20th Century-Fox Records made a generous monetary offer that included more creative freedom and an extra incentive: potential movie roles (a truly intangible carrot to dangle) through the label's movie studio parent company. Rather than fight it, Gordy agreed to let her go while making a deal with her new label guaranteeing him a percentage of royalties for the remainder of her original contract.

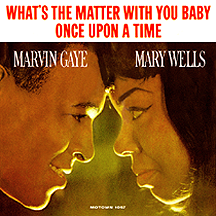

Earlier, Mary had recorded some duets with Marvin Gaye and two of those were hits on a back-to-back 45. "Once Upon a Time" and "What's the Matter With You Baby," released on the heels of "My Guy," each made the top 20, becoming her final two hits for the label (though she was the first of four female singers Gaye successfully partnered with over the next decade). In the summer of 1964, Motown closed the book on Mary Wells, moving forward into a more successful period, making an indelible mark on the music industry in the process. Gordy and company seldom brought up her name again until years later when the company's history became the subject of a number of books and television specials. Then, all wounds healed with time, she received her due as the singer some called "The First Lady of Motown."

Was it a mistake for Mary to leave the seemingly comfortable surroundings of Motown at the peak of her popularity? From a commercial standpoint it probably was; but artistic freedom is important to a true artist, and Mary wanted that freedom and felt she was entitled to be compensated fairly for it, so for her it was the right choice. Years later, she stated that she was glad she had made the move. At some point, though, she admitted she had been overly sensitive, her emotions had gotten out of control, and that if she had been more into the "business half" of it she probably wouldn't have left for what she perceived as greener pastures.

When Mary entered the 20th Century-Fox studios for the first time, she was nervous and uncomfortable in her new surroundings. To make matters worse, she had recently been confined to her home due to increasing symptoms of tuberculosis (related to those childhood illnesses), indicating her legal issues weren't the only reason she had been missing during the weeks when "My Guy" was breaking big. Eventually she got into the swing of things and enjoyed working with a new set of creative personalities, including Bernie Wayne, Lou Courtney and top-rate Chicago soul producer Carl Davis.

Still, it was a far cry from the heights she had achieved just months earlier at Hitsville. Her first single for the new label, "Ain't it the Truth," landed mid-chart near the end of the year. The early-'65 follow-up single, "Use Your Head," employed an all-star lineup of behind-the-scenes talent. Motown mainstay Barrett Strong (of "Money" fame) wrote tbe song with Charles Barksdale (The Dells' bass singer) and late-'50s R&B star Wade Flemons. Produced by Andre Williams and arranged by Riley Hampton, the track featured a cool performance by Mary reminiscent of her Motown recordings while verging on something more funky, and was her biggest hit for the label, yet all it could muster was a brief showing near the bottom of the top 40.

Other singles like "Never, Never Leave Me,""He's a Lover" and "Me Without You" were solid efforts and, perhaps, an improvement for those who preferred a grittier brand of soul music than the slick productions of Motown. But the hoped-for sales and airplay just didn't materialize, nor did anything resembling a film career. Mary left the label after a little more than a year but continued working with Carl Davis. In late '65 she signed with Atlantic Records, appearing on the Atco label with "Dear Lover," written and produced by Davis and Gerald Sims. Encouragingly it hit the R&B top ten in March 1966. Barrett Strong contributed more songs, including "Can't You See (You're Losing Me)" and "Such a Sweet Thing," but as it had been at 20th Century-Fox, Mary and her creative team were unable to maintain any kind of a streak.

Second husband Cecil Womack (former member of The Valentinos with his brother, Bobby Womack) was involved in the management and creative sides, and in 1968 she left Atco for Jubilee Records, notching several minor chart singles during a three-year stay, the best and most notable being "The Doctor" (penned by Cecil and sister Mary Womack). Two singles surprisingly released three years apart (in 1971 and '74) marked her association with the Reprise label, followed by several years of semi-retirement while she focused on family. Giving the music biz another go in 1982, she recorded "Gigolo" for Epic Records, a dance club hit and minor R&B charter.

All the while Mary's health was an issue. Having always been somewhat frail, she went through bouts with drugs, becoming dependent for long stretches, occasionally coming up for air long enough to make a few records and do some touring. I had tickets to see Mary perform in the late 1980s but was thrown for a loop with a bout of the flu just hours before the show. A friend was able to swing by and put the tickets to good use. He loved the show, telling me later that "she really knows how to work the room." I regretted the unfortunate timing that caused me to miss seeing one of my favorite singers in person but felt far, far worse when she was diagnosed with cancer soon after, resulting in her passing in July 1992, at just 49 years of age.

Mary Wells was an original. It's easy to imagine that her career at Motown might have taken on a routineness and run its course by decade's end. With that alternate scenario in mind, the reality of her efforts for other labels revealed a more prolific artist thinking outside the Detroit train of thought, and in the end we, the listeners, are all the better for it with a wider range of Wells styles and material to choose from. In the end, all of her music is quite enjoyable, though some shines less brightly than the recordings made during her peak Smokey Robinson period from 1962 through '64. At any rate it is what it is. And she will always be remembered as the sweet seductive songstress that she was.

NOTABLE SINGLES:

- Bye Bye Baby - 1961

- I Don't Want to Take a Chance - 1961

- Strange Love - 1961

- The One Who Really Loves You - 1962

- You Beat Me to the Punch - 1962

- Two Lovers - 1963

- Laughing Boy /

Two Wrongs Don't Make a Right - 1963 - Your Old Stand By - 1963

- You Lost the Sweetest Boy /

What's Easy For Two is So Hard For One - 1963 - My Guy - 1964

- Once Upon a Time - 1964

by Marvin Gaye and Mary Wells / - What's the Matter With You Baby - 1964

by Marvin Gaye and Mary Wells - Ain't it the Truth /

Stop Takin' Me For Granted - 1964 - Use Your Head - 1965

- Never, Never Leave Me /

Why Don't You Let Yourself Go - 1965 - He's a Lover - 1965

- Me Without You - 1965

- Can't You See (You're Losing Me) /

Dear Lover - 1966 - Such a Sweet Thing - 1966

- (Hey You) Set My Soul on Fire - 1967

- The Doctor - 1968

- Dig the Way I Feel - 1969

- Gigolo - 1982