RUTH BROWN

If there's one major misjudgment the Boston Red Sox organization has ever made, it happened in 1919, when the team's owner sold Babe Ruth's contract to the New York Yankees. Ruth was an outstanding pitcher and batter, a rarity in baseball. As soon as "The Bambino" got to New York, he began hitting home runs in numbers far outdistancing what any player had previously achieved; in 1921, the team made it to the World Series for the first time. In '23, Yankee Stadium was built in the Bronx, and to cap off their fresh start, the Babe led the team to its first World Series win. The Babe's arrival was the turning point, and eventually Yankee Stadium came to be affectionately known as "The House That Ruth Built." But what does all this have to do with the subject at hand, you ask? Just one thing: there's another instance of that particular phrase being used in popular culture. Baseball would be missing a large part of its legacy had the Yankees or Yankee Stadium never existed. Likewise, music would not be what it is today without another New York institution, Atlantic Records.

Ruth Weston grew up in Portsmouth, Virginia and showed an interest in jazz and blues at an early age, to the displeasure of her father, a church choir director. The oldest of seven children, at around age 15, during the latter part of World War II, she began sneaking out of the house to sing at an amateur night held regularly at the Booker T Theater (later the Attucks) on nearby Church Street in Norfolk, requiring a ferry ride each way across the Elizabeth River from Portsmouth. She left home soon after, back across the river to sing at the Big Track Diner in Norfolk, where she met trumpeter Jimmy Brown. Before long, they were married. She wouldn't be returning home.

Using Ruth Brown as her professional name, she began singing at any nightclub that would have her. Word got around that the young singer was good (and worked cheaply) and by age 19, in 1947, she had a regular job at a Detroit club. Lucky Millinder, one of the hottest bandleaders at the time (with several major "Race Record" hits under his belt including "Who Threw the Whiskey in the Well?" two years earlier), caught her act one night and hired her to sing with his band. A great opportunity, but one that just didn't pan out; she was fired a few weeks later in Washington, D.C. for what Millinder considered unprofessional behavior (the worst thing she was guilty of was acting friendly towards some of the customers). Alone in the nation's capitol, she landed a job singing at the Crystal Caverns jazz club ("Rendezvous of the Socially Elite"), where Blanche Calloway (jazz legend Cab Calloway's sister) became her manager. Before long, Atlantic Records chief Ahmet Ertegun caught her act.

Atlantic, in business less than a year in 1948, was struggling; its first hit record had yet to materialize. Ertegun and co-founder Herb Abramson, impressed with how seasoned the 20-year-old singer seemed to be, found they had a little competition: Capitol Records, already well established (successful in the Race, soon to be called R&B, field at the time with Julia Lee and Nellie Lutcher), was also interested. Atlantic guaranteed her a recording date in New York and Blanche managed to book her into Harlem's Apollo Theater near the same time, but fate stepped in. On the way to the big city, the two were in an auto accident. Ruth was badly injured and spent several months in the hospital. Ertegun and Abramson, though in a pinch when it came to money, covered her bills and, while she was still in her hospital bed, signed her to a contract. In May 1949, finally released from the hospital but wearing leg braces, she made her first recording for Atlantic, "So Long." She was on crutches when she sang at the session with Eddie Condon's band.

By this time, Atlantic had broken onto the charts with "Drinking Wine, Spo-Dee-O-Dee" by "Stick" McGhee and his Buddies and the instrumental "Cole Slaw" by sax man Frank Culley, both in the spring of '49. "So Long," written in 1940 by Remus Harris, Russ Morgan and Irving Melsher, was recorded that year by Cincinnati group The Charioteers. Ruth's version became the definitive one and was the label's third hit, and her first, in the fall. Then four singles followed with no results. Ruth had yet to find her own voice as she was mainly imitating her idols Billie Holiday and Dinah Washington (a breakout star in '48 and '49), doing mostly ballads. The song that made her reach beyond her comfort level, putting her career into high gear in the process, was "Teardrops From My Eyes," a Rudy Toombs composition. Toombs and Brown hit it off from the start; she has credited him with being a positive influence on her and the two worked closely together for the next few years.

"Teardrops From My Eyes" was no ordinary "hit" record. It was one of the runaway smashes of the early '50s, reaching number one on the R&B charts early in December 1950 and staying there (giving up just one week to Amos Milburn's "Bad, Bad Whiskey") through the final days of February '51. The uptempo "jump" tune (contrasting its subject matter), with Ruth's near-crying but exuberant vocal wail, made her a sensation and became the second Atlantic 78 issued on a 45, a format still a few years away from sales domination (the label's first 45 was Joe Morris and Laurie Tate's "Anytime, Any Place, Anywhere," a number one hit several weeks before Ruth's breakthrough).

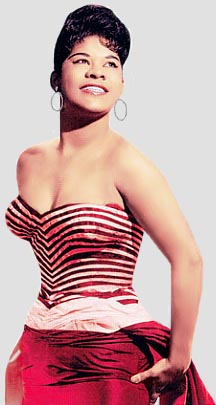

It's been entered into music lore that Frankie Laine, after seeing Ruth perform, nicknamed her "Miss Rhythm." Such an appellation could perhaps apply to any number of great singers...but in 1951, no one fit the name better than Ruth Brown, and it stayed with her throughout the years. Follow-ups "I'll Wait For You" (another Toombs tune) and "I Know" were hits, but both were cut in the mold of "Teardrops" and had relatively brief chart runs. A late '51 release missed altogether, then in the spring of 1952 she regained her glory with a slightly racy Rudy Toombs song, "5-10-15 Hours." Rudy had written it to say 'Just give me 5...10...15 minutes of your love,' but Abramson pointed out that a higher bar had been set for all things sensual with The Dominoes' smash "Sixty Minute Man" and they should adjust accordingly. It spent most of May and June at number one on the R&B charts. Her success had made all the difference for Atlantic Records those first few years, key to keeping them from going out of business (at least until The Clovers came along in '51). People started referring to Atlantic as "The House That Ruth Built," a nodding reference to Yankee Stadium and that other star with the same name.

The mambo became popular as a dance and musical trend in the early '50s and Ruth used a mambo beat for Toombs' "Daddy Daddy," which fell short of number one but had a two-month chart run in the fall. 1953 began with a record that is considered by many to be her signature song; Johnny Wallace and Herb Lance came up with "(Mama) He Treats Your Daughter Mean," which she resisted at first because the slow-tempoed lament the writers envisioned didn't fit her real life situation. The arrangement was changed to an uptempo one and Ruth recorded it, biting into the words as if she may or may not have been pleased with this mean man of hers. It was another number one R&B hit in March. Running a bit behind Dinah Washington when it came to racking up hits, by '53 she had pulled ahead, undeniably the hottest rhythmic female act of the era.

When she performed, crowd reaction was electric. Comedian Nipsey Russell often emceed her shows in the process of building his own nightclub career and said, "She tore the audiences up!" (one of the few comments he's made that wasn't in the form of a rhyme). "Wild Wild Young Men" (written by Nugetre, Ertegun's backwards-name pseudonym), one of Ruth's biggest hits in the summer of 1953, had a playfulness and assured vocal indicating she was growing as an artist. But getting a hit every time was a crapshoot, it seemed: the spunky "Love Contest" (a Charles Singleton-Rosemary McCoy song) fell flat in '54. She went all out with "Hello Little Boy," the screamin'est, sax-blowin'est record of perhaps her entire career. It, too, was an unexplainable no-show on the charts. But when she did hit, it was the big time, baby.

Back-to-back R&B chart-toppers came next: "Oh What a Dream," written by Chuck Willis (a future Atlantic star, coming off a nice run with Okeh Records at the time), her only ballad to reach number one, was subdued enough lyrically for Patti Page to cover it for the pop market in the fall of '54. Singleton and McCoy's uptempo dancer "Mambo Baby" followed it to the top in November, her fifth to reach number one. She carried the momentum into the new year; five singles hit the charts in '55, including "As Long as I'm Moving" (written by Jesse Stone as Charles Calhoun), Ted Jarrett's "It's Love Baby (24 Hours a Day)" and a duet (rare for Ruth), "Love Has Joined Us Together" with Clyde McPhatter, recent defector from The Drifters.

Ruth Brown's personal life became more complicated as the decade wore on. Divorced from Jimmy Brown, the question of who she was married to and just how many husbands she had is a mystery to most. She gave birth to a son, Ronald Jackson, whose father may have been saxophonist Willis "Gator Tail" Jackson, who led Ruth's backing band, but whether or not he was her second husband is up for debate and, to complicate matters, he may not have even been the father (rumor suggests it was Clyde McPhatter). It's fairly certain she was married for a time to another sax player, Earl Swanson, and had a son with him. There were likely one or two other husbands along the way, each of the marriages lasting no more than a few years.

Ruth's ongoing personal soap opera brought emotions for her to draw upon while singing, resulting in emotionally-charged performances that rang true. As black music was getting more and more airplay on larger radio stations, she began to reach a new audience. Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller's "Lucky Lips" and "This Little Girl's Gone Rockin'" (written by Bobby Darin and Mann Curtis) were top 40 pop hits in '57 and '58, but while other acts were making adjustments in order to fit into the new rock and roll trend, the jazz-influenced Ruth was losing touch with it; labelmate LaVern Baker, who came along a few years after Brown, was more in sync with where music was headed in the mid- to late-'50s and took her place as Atlantic's top female act.

While Dinah Washington, her rival from the 1949 through '55 period, was having a spectacular career resurgence in 1959, Ruth's own career was headed in the other direction. Her days with Atlantic were numbered, yet she did some of her best work as the decade came to a close. "I Don't Know," a Brook Benton-Bobby Stevenson song, found her in a pensive mood and had a haunting quality; it was a top ten R&B hit in late 1959. Chuck Willis's "Don't Deceive Me" was nothing less than a top-notch ballad and became her last top ten R&B hit in early 1960.

Atlantic Records and Ruth Brown parted ways in 1961 after a lucrative and mostly-rewarding 12 years together. She joined the Philips label roster and took a somewhat nostalgic approach while there, putting two songs on the pop charts in 1962: a remake of Faye Adams' 1953 hit "Shake a Hand" and a rockin' reboot of "Mama (He Treats Your Daughter Mean)" (the title adjusted slightly) that stood well on its own but ultimately lacked the raw magnificence of the original. After brief mid-'60s stints with the Decca and Mainstream labels, she settled into a far less glamorous life as a housewife and mother and at one time even drove a bus on Long Island to support her family.

I discovered Ruth's music during that down time in her career through Atlantic's History of Rhythm & Blues album compilation series, which included "5-10-15 Hours" and "(Mama) He Treats Your Daughter Mean," later putting together my own collection of her 1950s Atlantic 45s. For all I knew then, she was a once-great singer whose time had passed. Maybe she thought so too. Careers don't always fade away, though, and that certainly wasn't the case with Ruth Brown. She began recording again in the mid-'70s and took to acting as well, scoring a semi-regular role in the 1979 NBC sitcom Hello, Larry starring McLean Stevenson. A few TV and film roles followed, then she headed to Broadway for a run in Amen Corner in 1983 and the off-Broadway musical Staggerlee in the spring of '87. As "Motormouth Maybelle" in John Waters' hit 1988 film Hairspray, her profile took a huge leap and led to Black and Blue on Broadway in '89, for which she won the Tony award for Best Leading Actress in a Musical. Several months later she picked up a Grammy in the category Best Jazz Performance, Female, for her album Blues on Broadway.

NOTABLE SINGLES:

- So Long - 1949

- Teardrops From My Eyes - 1950

- I'll Wait For You - 1951

- I Know - 1951

- 5-10-15 Hours - 1952

- Daddy Daddy - 1952

- (Mama) He Treats Your Daughter Mean - 1953

- Wild Wild Young Men /

Mend Your Ways - 1954 - Love Contest - 1954

- Hello Little Boy - 1954

- Oh What a Dream - 1954

- Mambo Baby - 1954

- Bye Bye Young Men - 1955

- I Can See Everybody's Baby /

As Long as I'm Moving - 1955 - It's Love Baby (24 Hours a Day) - 1955

- Love Has Joined Us Together - 1955

by Ruth Brown and Clyde McPhatter - I Wanna Do More - 1956

- Sweet Baby of Mine - 1956

- Lucky Lips - 1957

- This Little Girl's Gone Rockin' /

Why Me - 1958 - Jack O'Diamonds - 1959

- I Don't Know - 1959

- Don't Deceive Me - 1960

- Shake a Hand - 1962

- Mama (He Treats Your Daughter Mean) - 1962