THE ROLLING STONES

I was a Stones guy back in the day. It's a dilemma dating back to the '60s itself: you were either a Beatles person or a Rolling Stones person. You can like both, but each individual has a preference for one or the other (the question has also been applied pitting Elvis against the Beatles). I was a fan of the Beatles back then (as now), but was perhaps a bit too young to understand any great significance in their work. As the decade progressed and I grew up, it was the Stones' blues-based sound I was drawn to. The "bad boy" image, a sharp contrast to my own sense of self, was something I found forbidden yet appealing, an emotion others have taken further through emulation. Later my fondness for the music of the Fab Four increased as I went through a phase, post-breakup, of digging beneath the obvious hit singles. But before that Mick, Keith, Charlie, Brian and Bill supplied the recipe for my poison of choice.

The flip sides of the early Stones 45s fascinated me, then came the inevitable album addiction, something rarely experienced by a "singles guy" like myself. England's Newest Hit Makers wasn't the first of their collections I discovered, as several had been released before my archival digging began. By the time I crossed paths with this debut U.S. album, I had learned much about the band's beginnings in the faraway land of England. In a nutshell, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards met in the early '50s during grammar school in Dartford, Kent, east end of London. They later went to different schools but met up again by chance in 1960, both in their later teens and obsessed with stateside rhythm and blues.

From way up the road in Cheltenham, Brian Jones came along and the band started to take shape in 1962 with Keith playing lead guitar and cowriting the occasional song, Brian playing guitar (when he wasn't goofing around with any other instrument that might be laying around) and Mick taking on the unlikely role of lead singer. Several potential bandmates came and went. Ian Stewart (from further up a different road in Surrey) clicked as keyboard player. South Londoner Bill Wyman signed on as bassist near the end of the year and the band was complete in early '63 when jovial Charlie Watts of Kingsbury in North London became the drummer and, according to Mick, the key member of the band throughout the years. Muddy Waters didn't realize it at the time, but his song "Rollin' Stone" supplied the group with its name.

Andrew Loog Oldham became the group's manager and producer a few months later (taking over for Giorgio Gomelsky, who had plenty of other irons in the fire) with the idea to position them as the antithesis of artists like the Beatles, Gerry and the Pacemakers and Frank Ifield, all red hot, reasonably clean-cut stars topping the charts at the time. Right off the bat Oldham demanded Stewart be thrown into the street, something about his image being all wrong. Well, now, Stu (as they called him) was tight with the other five; he instead was relegated to the position of road manager, session musician, buddy, pal, unofficial Stone, every bit as important as any of them, only with a smaller salary. Stewart was actually fine with it and stayed with the band as what you might call a "Silent Stone" until his death in December 1985.

After signing with Decca Records, the session for the first single took place. Chuck Berry's "Come On," right in the R&B zone (with a rock and roll lean), came out in June, backed by Willie Dixon's "I Want to Be Loved." Success came so easily! The Berry tune spent three months boppin' around the lower end of Britain's top 50 in the summer of '63. That thing about being the "bad boys" to the "good guy" Beatles, Pacemakers, etc. wasn't such a bad idea...but it didn't mean they couldn't be on friendly terms with the competition (particulary if they weren't posing any real threat to the dominance of those other bands, which they weren't...not yet, anyway). A large question mark must have hung in the air over the decision to do an unbluesy John Lennon-Paul McCartney song, "I Wanna Be Your Man," for release as the band's second single. It seems the Stones and Beatles had met and hit it off quite smashingly at the Crawdaddy Club in Richmond, Surrey. Besides, the song worked nicely either way, as an edgy Jagger-growler or fun-filled Ringo rouser, so everyone was happy in the end. Make that two hits for the Stones by the end of the year. "I Wanna" nearly made the top ten (still no real competition to those bigger acts, as the rivalry in 1963 was clearly between the Moptops and Gerry Marsden's Pacemakers, each with three U.K. number ones that year).

The group's origin notwithstanding, from the point of view of a kid from Los Angeles, The Rolling Stones were dark and aloof and just flat-out cool; moreso maybe than any recording act ever, with the possible exception of the aforementioned foursome. They entered the western hemisphere almost completely under the radar...who could have guessed that the K. Richards-M. Jagger writer credit on Gene Pitney's January 1964 single "That Girl Belongs to Yesterday" held a clue to the future of music? And it debuted on the U.S. charts the same week as a little tune called "I Want to Hold Your Hand"...which clearly had a hand in establishing the Stones in the 50 states a few months later, as well as every other British band who probably would have stayed close to home had the Beatles not ventured ahead to pry open the floodgates.

May 1964 rolled around and none of us Yankees (or Confederates for those still clinging to that bygone concept) were yet aware of the Rolling Stones excepting, of course, those who followed trade magazines like Billboard and Cash Box (no one in my elementary school was aware of them as far as I knew, but when I discovered those magazines later...well, here I am in a different century, banging on a keyboard in the middle of the night as a result). Unbeknownst to most of us, a single of "I Wanna Be Your Man" had already been released on London Records (the American arm of the U.K.'s Decca), backed with an instrumental, "Stoned" (written by the group but mysteriously credited to nonexistent songwriter Nanker Phelge), which would have made a good theme song for the band if anyone had actually heard it (the song's few lyrics, spoken by Jagger, included "Stoned...out of my mind!"); it was uneventfully rereleased in the U.S. about 25 years later.

The "Be Your Man" Beatles cover was used again for the flip side of the second single, so that song, at least, avoided a lengthy burial. The Stones, on an upward trajectory, had landed in the British top ten for the first time just weeks earlier with "Not Fade Away," exposing an appreciation for the works of rock and rollers in addition to the great blues geniuses; a Buddy Holly treasure taken from the B side of The Crickets' 1958 smash "Oh Boy!," it became the first Rolling Stones hit in the U.S., merely a mid-charter but an eventually cherished 1:48 masterpiece (when I finally saw them in concert for the first time after too long a wait, they opened with it).

The band's first album, The Rolling Stones, emblazoned with England's Newest Hit Makers across the top of the London Records cover (while the British equilvalent had only the cover photo and Decca logo), held many wonders mostly in the form of a tribute to R&B acts both older and reasonably current. Songwriter Bobby Troup's "Route 66," most famously a 1946 King Cole Trio hit, broke the band's predetermined format of blues and R&B. A second Dixon song, "I Just Want to Make Love to You" of Muddy Waters fame, was also the third single's B side, followed by "Honest I Do," originally a 1957 hit for Jimmy Reed, who to my ear holds the greatest influence over Jagger's vocal technique. Jimmy and Mick...brothers from another mother!

Slim Harpo's "I'm a King Bee," Berry's "Carol," the merely months-old Marvin Gaye hit "Can I Get a Witness," Gene Allison's optimistic "You Can Make it If You Try" and Rufus Thomas's whimsical "Walking the Dog" rounded out the album's remakes (Bo Diddley's "I Need You Baby" on the British edition was put on the shelf, replaced in the U.S. by "Not Fade Away"). Two Nanker numbers were included: instrumental "Now I've Got a Witness" (having nothing in common with the Marvin Gaye track besides the title) and "Little By Little." Then there was the first public appearance, since Pitney's single, of a composition by Jagger and Richards (his name shortened just a tad to Richard at Oldham's misguided insistence). "Tell Me (You're Coming Back)" became the group's first American top 40 hit, and before long Mick and Keith's names would be popping up more frequently among the ranks of the rock era's songwriting elite.

The group's first U.S. tour in June 1964 coincided with the release of the first album. The high point was a two-day stay in Chicago where nearly all of their time was spent at the studios of Chess Records, meeting Marshall Chess (at 22 the "next generation" of the family dynasty) and some of the artists they had idolized for a decade or more. All six Stones (Stewart included) recorded the majority of the songs that would make up the band's second long-player in a rare instance of a Chess session involving an outside act. 5x5, an EP in England, emerged as 12x5 in the States containing five originals (compared to the first LP's three), the Phelge-credited "Empty Heart" and instro "2120 South Michigan Avenue" (named for the address of the Chess offices and studios). Jagger and Richard boldly attached their names to three other originals, "Good Times, Bad Times," "Congratulations" and "Grown Up Wrong."

The rest of 12x5 proceeded much like the previous collection: Berry was again represented through "Around and Around," along with Wilson Pickett's "If You Need Me" and the '57 Dale Hawkins rocker "Susie-Q." The Drifters' recent hit "Under the Boardwalk" must have struck a chord with the group, resulting in its inclusion. Like before, a song dating from the 1940s found its way into the grooves; this time it was Jay McShann's "Confessin' the Blues," recorded in 1941 by the McShann orchestra featuring Walter Brown singing and Charlie Parker on alto sax. Two hits headlined the 12x5 collection: the first, "It's All Over Now," was a minor current hit for Bobby Womack's group The Valentinos; the Stones' version was rush-released and became their first U.K. number one a few weeks later, in July, just ahead of hitting the top 40 in the States. The second had been written by Jerry Ragovoy (using the pseudonym Norman Meade) and Jimmy ("I Don't Love You No More") Norman; the Minit Records version of "Time is On My Side" by "Soul Queen of New Orleans" Irma Thomas had been a favorite of Jagger and company and their version put them in the U.S. top ten for the first time in November 1964.

The Rolling Stones, Now! (simply titled No. 2 in England) came along in the spring of 1965, varying little from the successful formula. The obligatory Chuck track ("You Can't Catch Me") was there alongside Mick's heartfelt interpretation of Otis Redding's "Pain in My Heart," uptempo Barbara Lynn beaut "Oh Baby (We Got a Good Thing Goin')" and several other R&B gems. The Diddley tune deleted from the first album's U.S. edition made its belated appearance as "Mona (I Need You Baby)." I memorized them all. Another Willie Dixon track, "Little Red Rooster" (a late '63 hit for Sam Cooke), was number one in England in December '64 but didn't see a U.S. single release; by this time the band's 45s were strictly Jagger-Richard numbers. Four Stones originals on Now! made the grade: "Off the Hook," "Surprise, Surprise," single "What a Shame" and its A side, "Heart of Stone," a hit just prior to the LP's release.

"The Last Time" was the hardest-rocking track to date and returned the group to the top ten in May 1965 (and again to the top of the U.K. charts); flip "Play With Fire" grabbed some airplay and also hit the charts. Mick and Keith had hit a creative hot streak, often coming up with riffs and building songs around them while on the road. "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction" was one such song, the master take recorded during a stop at Hollywood, California's RCA studios in May. Considered by some the greatest rock and roll song ever, it became their first American chart-topper a couple of months later. Both hit singles were on Out of Our Heads, which hit the streets that summer. Soul shots by Betty Harris, Don Covay, Redding, Cooke and Gaye were done up Stones style. Seven Stones originals included "Satisfaction" U.S. flip "The Under Assistant West Coast Promotion Man" and U.K. flip "The Spider and the Fly."

I was familiar with most of the R&B originals by the time I heard the Rolling remakes. Phelge, Jagger and Richard were the names to look for if you wanted the really hot stuff on each disc. Late 1965 release December's Children (And Everybody's) satisfied my craving with "I'm Free," "Gotta Get Away," "The Singer Not the Song" and hit singles "Get Off of My Cloud" (another number one in November) and "As Tears Go By," which I'll admit wasn't a favorite since Marianne Faithfull's rendition (a hit a year earlier after Mick and Keith had first offered it to her) was thoroughly embedded in my brainwaves. Albums so far had come steadily about every four-and-a-half months (the modern concept of one album every three or four years unthinkable). Maybe it was time for a little breather...or maybe the next project needed more time. In just two years they had cranked out enough hits to warrant Big Hits (High Tide and Green Grass), a collection of greats that stayed on the charts for the following two years. "19th Nervous Breakdown" was an early-'66 smash making its debut on the compilation, while flip side "Sad Day" beautifully plumbed the depths of romantic despair and, with no appearance on an album, was nearly overlooked.

About seven months passed between December's Children and the next album. It was obvious from the get-go that they needed those extra two or three months. Serving as a preview, the deeply depressing "Paint It Black" hit the radio in May and shot to number one (there was clearly a public demand for musical misery). Aftermath is the Rolling Stones' masterpiece of the '60s, if not the band's entire career, while marking several firsts. Every track was a Jagger-Richard composition, which would be standard practice from this point onward. The recordings were in stereo, a better-late-than-never development considering the technology had been around for at least eight years. The entire session was held at the RCA studio in Hollywood with engineer Dave Hassinger from the "Satisfaction" session. "Paint It Black" led things off, "Stupid Girl" reminded me of one or two "privileged princesses" I knew and "Doncha Bother Me" became a well-worn phrase. Unfamiliar instrumental sounds entered my life through this album; marimbas, a dulcimer, far-out slide guitar effects, "Flight 505" with its back-of-the-room piano intro, the jangliness of "High and Dry" and the eleven minutes of "Going Home," which led to the task of listening over and over in search of dirty words my classmates claimed were in there somewhere. Prim-and-proper powdered-wig radio hit "Lady Jane" was included ("Mother's Little Helper," its 45 A side, wasn't, but the unrestrained exposé of pill-popping housewives led off the U.K. edition of the album).

"Under My Thumb" brought the Stones into territory conquered by the Beatles two years prior; the Aftermath album cut received massive radio airplay, more, perhaps, than many hit singles of the time, helping increase appetites far and wide for the band's music. Mid-'66 for the Stones was not unlike early '64 had been for the Fab Four, only without the sudden burst of energy, as we were already quite familiar with the group. L.A. deejay Humble Harve of KHJ was open about his love for the group, particularly their blues bent; whenever a Rolling Stones song came on the radio (and many did), a pre-recorded clip of Harve shouting "Stones!" would blast over the intro.

Someone pulled a fast one on us when a "new" song hit the airwaves that summer; "Fortune Teller" was the latest and greatest to those unfamiliar with its origin. The Naomi Neville tune was first a Benny Spellman flip side (backing his 1962 hit "Lipstick Traces," a good case for turning over every 45 to see what wonders might be hiding there) and was one of the earliest Stones recordings in 1963. I'm not sure if it happened first in Los Angeles (it may have broken out of Australia, where there was a single released), but the song was huge, going so far as to reach number one on KRLA's "all request" chart (which had replaced their regular Tune-Dex) in September '66. Attempts to buy the thing met with frustration until the studio version was tacked onto Got Live if You Want It! near the end of the year, with overdubbed screaming audience effects (the album was presented as a live concert at London's Royal Albert Hall but was actually pieced together from several sources, live and studio). The sizeable exposure of "Fortune Teller" in some regions resulted in a charted version by San Diego garage band The Hardtimes in December.

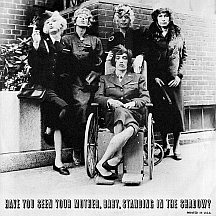

"Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow?" came in the fall of '66 with a another non-LP blast of blues on the flip, "Who's Driving My Plane." The needle on my record player ground down that side of the 45. Right before New Year's Eve, a new "exclusive" was touted with hourly airings. The less-than-honorable intentions in the lyrics of "Let's Spend the Night Together" gave the "old folks" (over 35, let's say) an excuse to want to exile the bad boys, but the result was merely a ban on the song. Stations flipped the record over and "Ruby Tuesday" hit number one two months later. It was a hot two-sider, even if the intended hit lacked exposure (Ed Sullivan made them sing it as 'Let's spend some time together' on his show in January and they complied, good fellows respectful of their elders in spite of any so-called image). The two songs were on Between the Buttons with ten others, all penned by Jagger and Richard, though Jones most likely gave considerable input; "All Sold Out" was my fave, while "Connection" got the most Southern Cal airplay.

Flowers appeared that summer under suspicious circumstances. The songs didn't hang together as well as the selections on other albums but there were some great ones nonetheless; "Out of Time" (a version by Chris Farlowe in the summer of '66, produced by Mick, was number one in England, top ten in L.A., no-show on the national U.S. charts) and "Take It or Leave It" were leftover Aftermath tracks. "Ride On, Baby" and "Sittin' on a Fence" came from the same sessions. "Back Street Girl" and "Please Go Home" had been on the U.K. Between the Buttons. I suspected right off that this was the case and even guessed correctly which was which from the distinctly different sound of each album. "Ruby" and "Let's Spend" were baffingly repeated from the previous LP (I would have chosen "Fortune Teller" and some other unreleased track).

"Dandelion" and "We Love You" came in the fall of 1967 as a stand-alone single, the latter considered by some as an answer to the Beatles' "All You Need is Love." It featured backing vocals by Lennon and McCartney and a sound effect of a slamming jail cell door at the beginning alluding to the group's drug bust that year though it had nothing to do with the song's lyrics. Omnipotent shotcaller A. Loog parted ways with the group around this time (having sold his management rights to New Jersey-born music biz huckster Allen Klein the previous year). Abandoning any remaining traces of the blues, Their Satanic Majesties Request was released near the end of the year, immediately seen as an imitation Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, though comparisons to the Beatles classic are tenuous; either way, my attention flagged. The new, psychedelic Stones had gotten off to a shaky start.

"In Another Land" was taken from the album and released as a Bill Wyman single, the only Rolling Stones 45 credited specifically to its lead singer. "She's a Rainbow" was the bigger "Majesties" hit in early '68. "Jumpin' Jack Flash" rocked hard and hit big in the summer without an album appearance. "Street Fighting Man" faltered in the fall but its album, Beggars Banquet (produced by Oldham's replacement, New Yorker Jimmy Miller), with more of a blues base (their forté!), was a considerable improvement over the previous LP.

Then Brian Jones left the band. It wasn't that he wanted to, it was just that his drug use had gotten the better of him. An open invitation from the others to return when he felt ready went unrealized; he was found dead in the swimming pool at his home in Hartfield, East Sussex in July 1969 at the age of 27. His was not the last Stones-related tragedy of 1969.

Another 45-only track, "Honky Tonk Women," dominated radio in the summer of 1969, their fifth U.S. chart-topper that, according to its chart run, is the band's biggest hit of all time. A second greatest hits collection, Through the Past, Darkly (with a then-unheard-of octagon-shaped cover) covered every hit starting with "Paint It Black," marking the first appearance on an album for some of the already substantially exposed tracks. In December, Jones' eventual replacement Mick Taylor debuted as guitarist on Let it Bleed, prompting his defection from John Mayall's Bluesbreakers. The band's final album of the '60s included "You Can't Always Get What You Want" (a big production number featuring London's Bach Choir, already familiar as the flip of "Honky Tonk Women"), "Gimmie Shelter" (featuring Merry Clayton, the first of several female R&B singers who would become a staple of the band's tours) and one of the few non-Stones tunes since their early efforts, "Love in Vain," originated in 1937 by Robert Johnson (a major influence on Brian, Mick and, most notably, the guitar playing style of Keith Richard, who was still several years away from reinstating the "s" at the end of his professional name).

The infamous December 6 concert at Altamont Speedway, east of San Francisco near Tracy, California, coincided with the new album's release. Members of the Hells Angels were hired as security guards...unfortunately, no one bothered to provide added security to keep an eye on the Angels. Several attendees were beaten and one was killed. Documentary filmmakers Albert and David Maysles and Charlotte Zwerin were on hand and the resulting film was beyond any original concept they could have had; a concert film on the one hand, an allegory on violence and brutality on the other. Gimme Shelter (the spelling changed slightly from the 'War, children, it's just a shot away...' song that inspired the title) was released a year later and remains a stark reminder of the turbulence of late 1960s music culture.

As the 1970s began, The Rolling Stones disappeared. Or at least it seemed that way to me. So many of the hot British bands broke up around that time, apparently unable to transition to the new decade. The Beatles made headlines when they disbanded. The Yardbirds, The Zombies, The Animals and The Dave Clark Five called it quits. Solo artists like Dusty Springfield and Donovan seemed to disappear. For all I knew the Stones had also gone away forever, just as the '60s inevitably had to. Maybe it had something to do with Brian's death, or the Altamont skirmish. 1970 went by quietly. Good news...turns out they were only in transition, separating from Klein and taking complete control of future endeavors. Suddenly in spring 1971 the band was back (for good!), sporting an outlandish new "lips and tongue" cartoon logo designed by graphic artist John Pasche (who admitted it was based on Jagger's "look") that would forever be krazy-glued to the image of "The World's Greatest Rock and Roll Band."

NOTABLE SINGLES:

- I Wanna Be Your Man /

Stoned - 1964 - Not Fade Away /

I Wanna Be Your Man - 1964 - Tell Me (You're Coming Back) /

I Just Want to Make Love to You - 1964 - It's All Over Now /

Good Times Bad Times - 1964 - Time is on My Side /

Congratulations - 1964 - Heart of Stone /

What a Shame - 1965 - The Last Time /

Play With Fire - 1965 - (I Can't Get No) Satisfaction /

The Under Assistant West Coast Promotion Man - 1965 - Get Off of My Cloud /

I'm Free - 1965 - As Tears Go By /

Gotta Get Away - 1966 - 19th Nervous Breakdown /

Sad Day - 1966 - Paint It Black /

Stupid Girl - 1966 - Mother's Little Helper /

Lady Jane - 1966 - Have You Seen Your Mother, Baby, Standing in the Shadow? /

Who's Driving My Plane - 1966 - Let's Spend the Night Together /

Ruby Tuesday - 1967 - Dandelion /

We Love You - 1967 - In Another Land - 1967

by Bill Wyman - She's a Rainbow /

2,000 Light Years From Home - 1967 - Jumpin' Jack Flash /

Child of the Moon - 1968 - Street Fighting Man /

No Expectations - 1968 - Honky Tonk Women /

You Can't Always Get What You Want - 1969